Uzyskaj dostęp do tej i ponad 250000 książek od 14,99 zł miesięcznie

- Wydawca: Mimesis

- Kategoria: Literatura popularnonaukowa•Nauki ścisłe

- Język: angielski

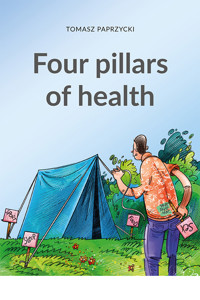

The author of the book—graduate of the Medical University of Poznań, Osteopathie Schule Deutschland and the European Academy of Sport Osteopathy—opens his guide by stressing how deeply it annoys him when, during holidays or birthdays, he hears the usual wishes: “Health! As long as you have your health, everything else will somehow work out.”

As if health were something we have absolutely no influence over, like the weather or winning the lottery.

Of course, he agrees with his patients and with the people who follow him on social media that we don’t have complete control over everything related to our health—because, as he puts it, some people start off already running uphill.

Still, he argues—drawing on both his knowledge and his hands-on clinical practice—that our everyday choices have the greatest impact on our health. Regardless of congenital issues, Apgar scores, age, or sex, human health rests on four powerful pillars.

And this guide is all about those pillars, and about how movement, sleep, proper nutrition, and… sex (and, as the author notes, a few other pleasures as well) shape our health every single day, again and again.

Ebooka przeczytasz w aplikacjach Legimi na:

Liczba stron: 304

Rok wydania: 2025

Odsłuch ebooka (TTS) dostepny w abonamencie „ebooki+audiobooki bez limitu” w aplikacjach Legimi na:

Podobne

Tomasz Paprzycki

Four pillars of health

Editor: Kamila Recław

Proofreading (of Polish version): Dorota Filip

Illustrations: Mariusz Sopyłło

Translation: Kamila Nowak

ISBN: 978-83-977714-7-5

Publishing partner: :

Copyright © Mimesis s.c. 2024

First edition

All rights reserved. Unauthorised distribution of all or part of this publication in any form is prohibited.

Reproducing it by photocopying, photographing, or copying the book to film, magnetic, or other media infringes the copyright of this publication.

This book offers guidance and information on healthcare. However, it should not replace professional advice from aphysician, physiotherapist, osteopath, or dietitian.

If you suspect you have amedical condition or are aware of one, consult aspecialist before starting any health improvement or treatment programme. Every effort has been made to ensure the information in this book was accurate and up-to-date at the time of publication.

Neither the publisher nor the author accepts any liability for health outcomes resulting from the use of the methods described in this book.

Gdańsk 2024

Table of contents

By way of introduction

PILLAR I

Physical activity

Physical activity and sport

How much should one move?

Which activity sounds best?

Mistakes in the sitting position

Does sport equal health?

Regeneration

Musculoskeletal disorders

Migraines

So-called Widow’s Hump or Dowager’s Hump

Tinnitus – ringing, clicking, buzzing, etc. in your ears

Scars

PILLAR II

Nutrition

Your gut has a mind of its own (The gut as the second brain)

Cortisol — the Stress Hormone and Survival Response

Chronic Stress

Adrenal Function Tests

The ‘Magic’ of Osteopathy

Reflux (gerd)

Bloating

Constipation

Diarrhoea

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

Hemorrhoidal Disease

Cholesterol

Poop – The Stinky Blessedness

Urine

Farting

Microbiota – The Bacterial Kingdom

Prebiotics

Probiotics

Antibiotics

Parasites

Microbiome Reset Program

Intermittent Fasting

Supplements

Vitamin D

Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Curcumin

Lactoferrin

Magnesium, Selenium, and Zinc

Spirulina and Chlorella

Supplements vs. Medications

Enemies of Your Body

PILLAR III

Sleep

Light – The Sleep Regulator

What Happens When You Sleep?

Sleep Disruptors

How to Improve Sleep Quality

Create a Bedtime Ritual

The Importance of Good Sleep

Do the Pillow and Mattress Matter?

Snoring

Taping the mouth at night

PILLAR IV

Sex

How Does Sex Affect Our Body?

Phases of Sex

Masturbation

Premature Ejaculation

Painful Intercourse

Testosterone

Hobby

Vagus Nerve

Breath

Lymph

Hypothyroidism (thyroid insufficiency)

Immunity

Laughter

Hiccups

Sneezing

Chewing Gum

Joint Cracking

Coffee

Yerba Mate

Non-Alcoholic Beer

Equipment for Self-Massage – Hype or Help?

Overuse of Medication

Osteopathic Exercises

Czakalaka Challenge

Czakalaka Challenge

By way of introduction

It has always greatly annoyed me when, on various holidays or birthdays, Ihear wishes like: ‘Cheers to your good health! As long as you’ve got your health, everything else will fall into place.’ As if health were something beyond our control, like the weather or alottery win, and something we must wait for as adivine gift. Of course, Iagree that we cannot control every aspect of our health entirely. Some people struggle from the very beginning because they were unfairly born with genetic diseases or congenital disabilities. Moreover, we spend the rest of our lives in apolluted and irradiated environment, or our health is taken away by others, either by infecting us with pathogens or through various types of accidents.

Nevertheless, it is essential to recall that your daily choices greatly influence your health. Yours! Not your mother’s, grandfather’s, brother-in-law’s, or your dog’s. Suppose you neglect to keep your body active, consume adiet high in sugar, drink alcohol every weekend, remain consistently sleep-deprived, and lack time or space for hobbies. In that case, even if someone sincerely wishes you good health every day, their wish will never come true. Regardless of congenital issues, Apgar scores, age, or gender, human health relies on four fundamental pillars.

When Iask my patients what being healthy means to them, Ioften hear in reply: ‘I am healthy when nothing hurts me’. Ihear from runners that health means running twenty kilometres with ease, and for my oldest patient, who will be turning one hundred in two years, being healthy means being able to keep the fork in her hand throughout the whole lunch. With age, people’s definitions of health change, but feeling pain or its absence should not be their sole determinants. Some individuals experience no painful symptoms whatsoever, yet struggle to put on their shoes without ashoehorn, suffer significant shortness of breath after climbing ten stairs, find defecating once aweek agreat effort, or have difficulties falling asleep without aglass of wine in the evening, waking up several times during the night. Can we consider these individuals healthy? Imagine ahealth ladder with ten rungs. Standing in front of it with our feet below the first rung indicates we are perfectly healthy, while climbing to the tenth rung signifies astate of severe, advanced illness. Very often, pain appears around the fifth rung. In contrast, the bodily signs of declining health start with the first one. At that stage, the body sends us silent warning signals, even before pain appears! These may manifest as strange tingling sensations, slight bloating, stiffness — especially in the morning — reduced joint mobility, difficulty getting out of bed in the morning, unusual colours of urine, stool, or tongue, eyelid twitching, needle-like prickings in the stomach, infrequent bowel movements, dry or discoloured skin, brittle hair and nails, and many, many more. The longer we ignore these silent warning signals, the higher we climb the ladder of health, and PAIN becomes merely amatter of time. In most cases, we wake up from our apathy only because of pain, which eventually motivates us to take steps to improve our health.

The best way to address this issue is to identify the cause of the pain. You might experience neck pain because your computer is positioned on the right side of your desk, leading you to sit all day with your head tilted to the right, or because it is placed too low, forcing you to lean forward. Reflux could also be achronic cause of your discomfort, or your habitual shoulder shrugging as astress response. What are the solutions? Here are some options: adjusting your posture, managing reflux, or practising stress reduction. Unfortunately, another problem arises because most people tend to seek alternative remedies. The most common choice, especially among men, is to do nothing and wait for the pain to pass. The human body has an incredible capacity for self-healing; it constantly seeks homeostasis, astate of balance, and often the pain subsides on its own as the brain ultimately finds relief. However, this approach usually relies on the phenomenon of compensation. For instance, constantly looking to the right causes the cervical vertebrae to rotate to the right. Not aproblem—let’s rotate the thoracic vertebrae to the left; the rotations balance out overall. This is how our brain functions. But this solution only lasts about amonth, after which the lower back will respond to the imbalance.

If we ignore the symptoms, our brain begins to find other ways to compensate, such as rotating the hips this time. As aresult, our margin of error decreases. Since the brain has no more room for adjustments, the pain often persists instead of disappearing. Unfortunately, this is usually when many people turn to solution number two: painkillers. For many, it’s the immediate go-to because they can’t imagine waiting for relief naturally. Options such as paracetamol, ketoprofen, ibuprofen, diclofenac, and other medications can help alleviate the situation without worsening it. They keep us on the fifth rung of the health ladder, providing temporary relief and boosting confidence that we’re better. However, if we repeat this pattern of ‘treatment’ over the years—sometimes increasing doses, switching to stronger medicines, or overdosing—we gradually climb higher on the ladder. Eventually, we reach the ninth or tenth rung, where serious health issues like diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, stroke, heart attack, or atherosclerosis await us. At this point, climbing back down the ladder becomes along, arduous journey and sometimes even impossible.

For me, being healthy means maintaining abalance between the four pillars of health, or, if you prefer, the tent ropes or table legs. Even one rope that is too tight or too slack, or one leg that is too long or too short, will cause the tent and the table to tilt and topple. Ialso disagree with the idea that PESEL No. is to blame for all of this. Patients often describe their visits to the doctor and the diagnosis with aproverb: ‘At your age, you must already feel pain’. Before thirty, men seek illness; after thirty, illnesses seek men. As we age, the tent ropes may become thinner and frayed, and woodworms may gnaw the table legs, but this does not prevent the essential balance from being maintained. The second saying Istrongly dislike is: ‘Old age is adisease that you die from’. It often takes years to climb the ladder, often due to long-standing, unhealthy habits. You don’t develop diabetes from eating adoughnut on Fat Thursday, arthritis from sitting in front of acomputer for aday, or cirrhosis from just one beer. But if you do these things for many years, then indeed, old age will become your disease. The long-term imbalance in youth means that in old age, you may no longer be able to stand upright. And you should! Japanese Yuichiro Miura summited Mount Everest at seventy-five. Fauja Singh from India ran the Edinburgh marathon in 2011 as acentenarian! Your body is an extraordinary machine if you take care of it.

A focus on the eighth sense.

The examples above are, of course, quite extreme, but they also offer encouraging evidence that old age can be accompanied by good health. However, we need afew skills to follow in their footsteps and stay healthy for as long as possible. This is where the so-called eighth sense becomes avital element. In addition to the five basic senses (sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch), we have asixth, which is intuition; aseventh, proprioception (the body’s ability to sense its position and movements); and an eighth sense, interoception, which is defined as feeling everything that happens inside our body. Iactively expand this concept to include noticing the silent warning signals that the body sends between the first and the fourth rungs of the health ladder. Well-developed interoception allows some people to accurately sense their heartbeat, recognise any changes in its rhythm, be aware of their breathing, and identify which muscles they use to draw air into their lungs. Such individuals pay attention to signals from their intestines, are aware of tensions in their body, and notice tingling, numbness, or twitching that appears. They interpret these signals as warnings of imminent pain and monitor for changes in the consistency and colour of their stool and urine, as well as alterations in their skin, hair, and nails. Conversely, many people—unfortunately, the majority—have poor interoception. For them, reading silent signals is impossible; they neglect observing their bodies, and the loud warnings from the brain, such as ongoing back pain for twenty years masked by painkillers, go unnoticed. Of course, this does not mean one should visit the doctor every time their elbow itches. The first step is to learn to recognise silent signals and become more body aware. The next step is to respond correctly: which symptoms can be ignored, which ones require closer observation, and which need immediate consultation with aspecialist. Ihope that this book will be of help to you by sharing my knowledge and the experience Ihave gained through years of medical practice.

Every human body consists of five major systems. We exclude the mechanical system, i.e., our muscles and joints; the circulatory and respiratory systems, including the heart, lungs, and blood vessels; the digestive system, i.e., our internal organs; the nervous system, comprising the brain, spinal cord, and nerves; and the biopsychosocial system, i.e., our body and mind. As Imentioned, human health relies on four key pillars that support our well-being, because each of these pillars influences all five major systems. Most of my patients visit me due to mechanical system issues, such as back, hip, or knee pain. However, my task is to diagnose which system is responsible for the problem. Quite often, the source of pain is in acompletely different system or results from asignificant imbalance between the pillars of health.

Since you’re reading this book, you must be interested in the subject of health and committed to taking your own responsibility by adopting healthy habits. Let’s get started! First, you’ll be introduced to some basic knowledge, and at the end of the book, you’ll find the thirty-day ‘Chakalaka challenge’, which could transform your life and make you feel alive again. All you need to do is follow and carefully implement the plan, step by step.

PILLAR I

Physical activity

‘The physical activity replaces many medicines; no medicine can replace physical activity’.

(Wojciech Oczko, Polish physician practising in the 16th (!) century)

It’s not that we stop moving because we get old, but that we grow old because we stop moving.

(Father of aerobics, Dr. Kenneth H. Cooper)

Physical activity and sport

One of the first challenging questions Iask every patient in my practice is: ‘How are things with your physical activity?’. The vast majority sigh heavily and admit they don’t get enough movement and, needless to say, they list awhole bunch of excuses. Meanwhile, physical activity is the central pillar of health, affecting every one of our body systems and, consequently, the other three pillars. Many so-called ‘hopeless cases’, that is, patients to whom massages, manual therapy, acupuncture, leeches, or alpaca fur wraps did not help, found relief in the simple act of moving their bodies. Physical activity is asign of life. Thousands of years ago, before the invention of computers, telephones, or even electricity, people were constantly on the move, exploring new territories, searching for food and water. They spent most of the day moving and rested in the evening. They indeed died, as antibiotics or vaccines to protect our health had not yet been developed. Today, we live longer because our immune systems are well-supported, but the lack of movement and the daily car-office-car-sofa routine insidiously and slowly harm us.

How much should one move?

What absurd times we live in, when watches (specifically smartwatches) count the steps we take each day and check whether we reach the 10,000-step target, or beep loudly whenever we remain still for too long. You won’t need asmartwatch if you follow the rules outlined in this book.

Once, Iwas visited by atypical pen-pusher, Mr Eugene.

- Mr Tom - he struck up aconversation - Isit at work for eight hours. Additionally, Icommute for half an hour one way. How much should Imove after work to compensate for these motionless hours?

- There is no such amount of movement, Ireplied.

- How come? - he asked, surprised.

- Well, sitting for nine hours causes some irreversible changes. You need to move DURING work, not only AFTER.

On another occasion, Mrs Aldona, the manager of alarge corporation, visited my office.

- Mr Tomasz - Iheard awoman’s voice. - What is the best sitting position?

- There isn’t such athing - Ireplied.

- Come again? - She asked in disbelief.

- The best sitting position is afrequently CHANGED POSITION - Iannounced. – Regardless of whether you perform your tasks sitting, standing or working physically, the key is to change your position regularly.

Undeniably, some positions can cause injury very quickly, while others do so gradually; however, no single posture allows us to work for nine hours without harm. Ialways give the same answer to the question of whether it’s better to sit on alarge ball or aspiked cushion, or whether akneeler or astanding desk is preferable: it’s best to alternate each of these options every hour. Additionally, clerks should get up and walk every half an hour; optionally, they may do twenty jumping jacks, while standing or physically active workers should sit for half aminute or use aso-called Slavic squat.

Our bodies handle prolonged static positions better when we engage in more vigorous movement beforehand. Scientific research shows that the ideal amount of physical exercise is about 1.5 hours of intense activity twice aweek. Not more and not less, but for some, that remains sufficient. Of the week’s one hundred and sixty-eight hours, THREE (!) should be devoted to intense exercise. Throughout the rest of the book, Iwill often refer to this fact as Idiscuss various diseases.

Which activity sounds best?

When Imanage to persuade an average clerk that we cannot progress without implementing physical activity, Iusually hear that magic question, ‘All right, but what should Iactually do? What will work best for me?’

That’s when Ioutline my four iron rules:

Iron rule number one: you have to enjoy it!

Everyone should choose something that brings them happiness. Otherwise, they will quickly become frustrated and stuck at their desk. If someone hates running or swimming, Inever force them to do it.

Iron rule number two: you have to get tired!

Patients often attempt to present themselves as healthier than they truly are. When Iask about their physical activity in my office, they enthusiastically mention their achievements, such as walking the dog twice daily, running up and down stairs at home, chasing children in the garden, walking two hundred metres to the bus stop each day, or regularly playing checkers with abrother-in-law. That’s lovely, Isay at the time, but you need some more sustained activity that lasts about an hour and ahalf, raises your heart rate significantly, speeds up breathing, causes sweating, burns glucose and fat, fatigues muscles, makes you thirsty afterwards, and helps you forget your life worries. That’s precisely what we need.

Iron rule number three: Counterbalance what’s at work!

Often, when Iask desk officers about physical activity, they boast: Icycle alot! That’s lovely, Isay; you can get tired on abike, but you may still enjoy it. However, it still involves asitting position. Cycling or swimming is an excellent choice for those with astanding or physically demanding job. However, people who sit alot at work should opt for activities that activate their legs, such as running, football, basketball, tennis, squash, Zumba, fitness, aerobics, Tabata, volleyball, or martial arts. There’s awide variety of options.

Iron rule number four: regularity!

Once you have found an activity that suits you, there is only one thing left: do it regularly. If you’ve been through aperiod of inactivity and abreak from intense exercise, start at aleisurely pace, once aweek, and gradually increase the intensity, allowing your body to adapt to your new lifestyle. The optimal amount of exercise, as mentioned above, is 1.5 hours twice aweek. However, this is an individual issue, and it may be more or less. It is essential to avoid overexercising at the beginning and going to extremes. People who have evolved from a‘couch potato’ type of person to an ‘Ironman’ doing seven workouts aweek represent agroup of habitués of physiotherapy and osteopathy clinics.

At the core of these four rules, one must select an individual physical activity suitable for them.

Mistakes in the sitting position

The inquisitive reader is undoubtedly eager for the continuation of the earlier discussed topic: some positions damage us very quickly, while others harm us gradually. Having listened to thousands of patients visiting my clinic and analysed how they sit in their chairs, Idraw ableak conclusion: most of them make five simple mistakes that damage their health rapidly.

Forward head posture (FHP)

I call this posture the ‘Curious Turtle Position.’ If, in profile, you resemble aturtle that extends its head half ametre beyond the shell, this is one of the most harmful positions for health. This mistake is an easy cause of neck pain, occipital headache, or hand numbness, as well as being one of the leading causes of so-called widow’s hump or dowager’s hump. The most common reason for this position is that the computer is placed too low while working, long-term use of asmartphone, or eyesight problems (to see the details that are blurred, we often tilt our head forward).

Lack of elbow support

Suppose we use acomputer mouse, atelephone, acrochet hook, or perform any manual work during which the hand is even minimally raised for aprolonged period, even slightly. In that case, we increase tension in the neck and back muscles.

If the arm remains extended forward for aprolonged period (e.g., when the computer mouse is far away), the shoulder blade will move forward, and the rotator cuffs may be affected. Symptoms such as arm numbness may frequently occur.

Twisted position of abody

This error usually happens when your workspace is poorly arranged. If your computer isn’t placed directly in front of you but on the side, and you sit slightly turned, you create an imbalance in your body (one side shortens, the other stretches). Some people work across two, three, or even four monitors, so it’s worth knowing which one you use most often and trying to prevent long-term twisting to one side.

Asymmetrical leg positioning

Placing ‘one leg over another’ or ‘leg under the butt’ are the most notorious leg positions. Their worst effect is pressure on the blood vessels, which accelerates the development of varicose veins. There’s no harm in frequently moving the legs; every five minutes is sufficient. Unfortunately, humans tend to form habits; thus, in practice, legs are positioned most comfortably and switched due to numbness after awhole hour, only to return to their previous position for awhile.

Semi-reclining position

The coronavirus pandemic and lockdowns have forced many of us to work remotely, presenting the biggest challenge for those unable to establish an appropriate workspace at home. This has led to using sofas, armchairs, chaise longues, pouffes, and so on. The pandemic has sparked creativity in body positions that physiologists had never envisioned, and Irubbed my eyes in disbelief that someone had come up with such an idea. However, the semi-reclining position appeared most appealing; lying on asoft sofa with legs on atable or pouffe, and the computer on one’s lap. Some people also choose this option when sitting at their desk, as they slide down the chair until they reach asemi-reclined posture. It is anightmare for our spine, as it forces an unfavourable position of the sacrum and significantly overstrains the lumbar region, causing our head to move forward considerably.

If you want to slow down the process of body destruction when sitting for eight hours, make sure that the top of the monitor is at your eye level, and your head is aligned with your shoulders. Remember to support your elbows and keep the computer mouse as close to you as possible. Place the computer directly in front of you, and if you use more than one, make sure you turn to each side evenly. Try to avoid long-lasting body positions when your legs are placed asymmetrically. It might be agood idea to support your lumbar spine with asmall roller or invest in achair pad aimed to protect you from excessive hunching over, as it pushes your lumbar spine forward. Remember to stand up, walk around for awhile, bend your body to all sides, and do some jumping jacks at least every hour.

It is impossible to categorise all types of work, but the fundamental principles remain consistent. Frequently change your position and avoid repeating the same movements continuously. Even the simplest tasks can be performed in various ways. Whether you’re digging in the ground with ashovel, lifting cardboard boxes, or moving furniture, think of ten different ways to position your arms and legs and switch between them often. Remember to adhere to ergonomic principles, which involve keeping objects close to your body during lifting, stabilising yourself with your abdomen and glutes, generating pressure in the abdominal cavity, and using your legs instead of your spine. If everyone followed these guidelines, Iwould have eighty per cent less work in the office, and Imight need to earn some extra money elsewhere, perhaps in asupermarket, because people would be much healthier. Many patients do not require complex therapies; all they need is to identify the causes of their body’s deterioration and correct their habitual posture errors.

Does sport equal health?

Comparing health to afour-legged chair, it is crucial to understand that the main issue is balance. The ‘health chair’ of the average person is unstable due to atoo-short pillar of movement. Conversely, too long aleg, meaning too much physical activity, can also destabilise health. At this point, Iam obviously referring to competitive and professional athletes. That is why Idisagree with the statement: ‘Sport means health’.

One of the first sentences Iheard after starting my education at the European School of Osteopathy was: ‘If you want people to be healthy, they should be banned from competitive sport’. Personally, Ihave great respect for athletes who sacrifice their health and their time, which could be shared with their families, for preparation and training. They maintain strict training discipline, follow dietary regimes, cope with injuries, push their bodies and minds to the limits, all to achieve sports results: to run faster, throw further, jump higher, win amatch, or win achampionship.

Watching the athletics world championships, we envy the athletic, sculpted bodies of the runners. At the same time, few realise the enormous effort that went into their journey to success and the health risks they will face after their sporting careers end.

A notable fact is that the musculoskeletal system is often the least of the athletic problems. While it is true that recurring injuries, strains of tendons, ligaments, and muscle damage frequently cause athletes to take breaks from training, at the end of their careers, they often undergo numerous operations, usually involving endoprostheses for worn-out joints. However, sport also has adarker side and can harm the human body in many other ways.

Exercise-induced asthma

A fatigued athlete with rapid breathing often hyperventilates, leading to excessive carbon dioxide loss. Despite having ample oxygen, gas exchange becomes obstructed, causing tissue hypoxia. This substantial effort can result in symptoms such as exercise-induced asthma and shortness of breath. It is advised to breathe into aplastic bag for fifteen minutes after intense exercise—once every minute, for five repeats—to help retain carbon dioxide.

Urinary incontinence

This issue primarily affects female athletes. Due to the strong abdominal muscles at the front, acontinually tense diaphragm at the top, powerful back muscles at the rear, and weak pelvic floor muscles below, incontinence occurs at the bottom. It is often the main reason for ending acareer. Therefore, it is essential to include pelvic floor muscle training in sports regimes.

Leaky gut syndrome

Physical activity raises the body temperature. Frequent overheating and the chronic activation of thermoreceptors in the pelvis, along with the ongoing need to repair microtraumas from training, lead to an overactive immune system. This causes what is known as low-grade inflammation, the primary reason for the loosening of tight junctions between intestinal cells. Consequently, unnecessary energy is lost — instead of being used for faster running or throwing further, the body allocates energy to immune activity. The immune system, alongside the brain, is one of the most energy-consuming organs. Gastrointestinal issues such as bloating, constipation, diarrhoea, or abdominal pain may also occur. The protein zonulin maintains intestinal integrity, so astool test for antibodies against zonulin is used to diagnose intestinal permeability. In treatment, L-glutamine supplementation is recommended to enhance the permeability of intestinal cells.

To fully recover after intense training or competitions, our body requires about forty-eight hours, which is roughly two days. That’s why athletes who train twice aday, participate in contests and matches, and have only one day of rest per month are perpetually overexhausted. This is asimple way to address tiredness, not only physical but also mental, metabolic, and hormonal. This is why athletes’ lifestyles are so exhausting. Sports will always strain their bodies; therefore, the osteopath and physiotherapist play avital role in minimising the harmful processes. Those who focus on maximising regeneration time and develop their sense of interoception reduce their risk of injury and slow their rate of deterioration most effectively.

Regeneration

I used to think that professional athletes, such as football players who earn alot, are knowledgeable about recovery and serve as prime examples of its practical application. Later in life, Irealised that they, like ordinary non-athletes, stay up late at parties, drink alcohol, and eat pizza. Of course, not all do, and indeed to varying degrees. Nonetheless, it is precisely recovery—or the lack of it—that often influences success, the number of injuries, the duration of an athlete’s career, and their quality of life after retirement. Therefore, the following few sentences may serve as arevelation and inspiration for amateur athletes as well as professionals. Here are the fundamental rules of recovery:

Regenerative sleep

There is no better form of regeneration than deep, uninterrupted, healthy sleep. It is the third pillar of our health, and if you have issues with it or are particularly interested in this topic, you can now skip ahead to the chapter about sleep. Staying up all night at parties has nothing to do with regeneration.

Regenerative cold

The athlete, like everyone else, should be familiar with cold. It naturally stimulates our immune system, increases white blood cell count, lowers body temperature, improves tissue circulation, and calms the nervous system. Therefore, regular cold showers and baths are recommended.

Regenerative heat

In my opinion, cold is amore effective stimulus than heat and should be used more frequently, but visiting asauna can also offer many benefits. Heat relaxes muscles and speeds up the removal of metabolites and toxins by stimulating our natural filters – the liver, spleen, kidneys, and lungs. It can also be seen as aform of exercise for our thermoregulatory systems.

Regenerative Breath

Breathing is often the most overlooked aspect of human life, although it is simple, painless, free, and automatic. Yet, it proves to be apowerful tool that influences all of our systems – excellent for regeneration. Ihave written aseparate chapter about it for you.

Regenerative bodywork

What Imean here is not only regular visits to aphysiotherapist who will care for tired muscles and fascia, or to an osteopath who will improve blood circulation, the mobility of internal organs, drain the liver, and enhance the flow of blood and lymph through the body cavities, releasing the diaphragm. Iam also referring to self-work – doing exercises that improve joint mobility, stretching, and stabilisation, which are often neglected because we lack time in our schedules.

Regenerative movement

Paradoxically, athletes’ problem is that... they don’t move enough! It is common practice that, after two intense one-and-a-half-hour training sessions aday, they spend the remaining twenty-one hours of the day lying on the couch like lions on the savannah. The best way to alleviate soreness after training is through low-intensity movement, such as awalk, abike ride, or recreational swimming. This also relaxes the nervous system, since the body is doing something different from its daily training.

Regenerative support

When you are aseasoned athlete, the minor details count significantly. This is why various devices have been developed to accelerate recovery, including hyperbaric and normobaric chambers, compression massage devices, and CO2 masks for retaining carbon dioxide.

Musculoskeletal disorders

It’s not possible to stay healthy without abasic understanding of how the human body functions. There’s no chance to cover all musculoskeletal diseases here. However, over the years of my practice, Ihave noticed several recurring situations in which patients undergo unnecessary tests, visit the wrong specialists, or are subjected to needless procedures. Therefore, in this chapter, Iwill discuss your most common problems.

Discopathy

Two years ago, Arthur, atwenty-eight-year-old corporate worker and avid runner, visited me in my office.

- Mr Tom, - he said, - I’ve been suffering from back pain for two months. My doctor has told me not to run because the MRI scan showed athree-millimetre herniated disk in my lumbar spine.

- And did the doctor inquire carefully about the nature, circumstances, and variability of this pain? - Iasked.

- He did not,- was the reply.

- Did he at least perform orthopaedic diagnostic tests to confirm this hypothesis?

- No.

- Then how can anyone assume that this discopathy causes the pain?

- Idon’t know about that, Arthur shrugged his shoulders. The doctor recommended resting, painkillers, and swimming as aphysical activity...

After athorough interview and examination of Arthur, it was revealed that he had amuscle issue, and the pain disappeared after asingle treatment. Six months ago, he returned to me, this time with aproblematic elbow, but Isuspect the real reason for his visit was to share interesting information with me. Since our first consultation, the back pain has gone; therefore, he decided to repeat the MRI scan to check on his discopathy. He handed me the results, smiling broadly.

- Athree-millimetre herniated disc in my lumbar spine, he announced. - As it was, so it remains. And some degenerative changes have also appeared. But now Iunderstand that what is seen on an MRI scan is not necessarily the cause of my symptoms.

It is common practice to ‘treat’ adisc that shows no symptoms. Furthermore, scientific studies indicate that the size of the disc does not correlate with the symptoms. Some patients have an eight-millimetre herniated disc and no symptoms, while others experience very sharp pain with just aone-millimetre herniation. What is seen on the MRI must always be complemented with athorough interview and examination of the patient.

A disc, or intervertebral disc, is awatery pad located between the vertebrae. Twenty-three such discs can be found in the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spines. They consist of two parts: the jelly-like inside (water + proteins), called the nucleus pulposus, which is surrounded by astrong lining of collagen fibres, known as the annulus fibrosus. Discopathy is the general term for disk pathology, which has different phases. As the pressure in the nucleus pulposus increases, it begins to press inward on the surrounding annulus. Over time, it will start to deform, creating abubble known as aherniated nucleus pulposus, which can be measured with magnetic resonance imaging. The formation of such ahernia can be painful, but not necessarily; it may also happen that, as aresult of disc pain, we change our lifestyle, e.g., start sitting less, moving more, and the disk ceases showing symptoms, even though the hernia remains. The popular term ‘slipped’ or ‘ruptured disc’ refers to asituation when the collagen fibres of the annulus fibrosus rupture completely in one area, causing the gelatinous nucleus to spill into the spinal canal. This usually happens during asudden movement, lifting aheavy object or even sneezing. People then experience sharp pain in their back and especially in the leg, due to massive swelling and inflammation in the tight space around the roots of the spinal nerves, which form the sciatic nerve, among others. This is an extreme situation that most often ends in surgery or apatient’s several-week life break involving injections and painkillers while waiting for the sequestrum, i.e. split masses of nucleus pulposus, to be absorbed. If someone claims that they have aherniated disc simply because their back hurts occasionally, they are mistaken.

How do we know that the pain originates from the disc? Afew of the following characteristic sentences, heard from the patient, set off awarning light in my head, indicating active discopathy.

The pain intensifies in the morning

‘Dear sir, it’s fine in the evening, but every day Iwake up around five or six o’clock, and Ican’t sleep any longer because of the pain; Ihave to get up and walk.’ People are surprised – after all, they are lying down, doing nothing, so where is this pain coming from? It must be the pillow or awrong mattress...

‘While we doze, our discs hit the sauce,’ Ithink at that very moment. When lying down, the decompressed discs absorb more fluids and slightly increase in volume, and when we stand up and walk around during the day, they shrink again. That’s why aperson is taller in the morning than in the evening, even by one and ahalf centimetres! But if the disc is damaged and still absorbs fluids, the pain will worsen in the morning...

Pain during coughing and sneezing

The rise in abdominal pressure during these activities is asignificant trigger of disc pain. If the patient sneezes and coughs without difficulty, it is unlikely that their pain originates from adisc.

Pain localised centrally

When Iinquire about the location of the pain, patients readily and confidently point, usually with one finger, to a