Uzyskaj dostęp do tej i ponad 250000 książek od 14,99 zł miesięcznie

- Wydawca: Narodowy Instytut Fryderyka Chopina

- Kategoria: Literatura faktu•Autobiografie i biografie

- Język: angielski

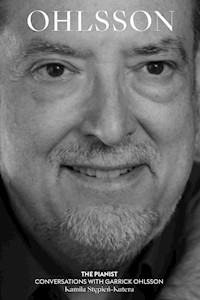

Conversations with the greatest pianists of the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries is a new book series of The Fryderyk Chopin Institute. Garrick Ohlsson – an outstanding pianist, the winner of the 8th International Chopin Piano Competition, is the main character of the first book in the series.

Ebooka przeczytasz w aplikacjach Legimi na:

Liczba stron: 344

Rok wydania: 2021

Odsłuch ebooka (TTS) dostepny w abonamencie „ebooki+audiobooki bez limitu” w aplikacjach Legimi na:

Popularność

Podobne

INTRODUCTION

The conversations with Garrick Ohlsson published in this book were held in February and April 2018.

Most of our meetings took place at the pianist’s home in San Francisco – a beautiful place, filled with the music of the nut-brown Bösendorfer in the living room and with the decorated frame of one of the mirrors capturing a sketched portrait of Paderewski alongside a likeness of Chopin. Everything – not least the generous hospitality of the host – produced a special atmosphere, just as a well-chosen venue and lighting create the ideal conditions for a piano recital.

During that February week Garrick Ohlsson played Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto at Davies Symphony Hall with the San Francisco Symphony conducted by Herbert Blomstedt, so his evening performances complemented for me the two afternoons we spent in conversation. Our last discussion, picking up where we left off, was held in Wrocław in April, the day after a recital comprising Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 28, Op. 101; two Etudes by Scriabin (Op. 65, no. 1 and Op. 8 No. 10); his Prelude (Op. 59 No. 2); his Poème (Op. 32 No. 1); his Sonata No. 5 (Op. 53) and Franz Schubert’s Sonata in A major (D. 959). We devoted much time to the treatment of this last piece, discussing various details of Ohlsson’s interpretation.

Garrick Ohlsson is an unparalleled conversationalist, just as he is an unparalleled pianist – mindful of the choices he makes, erudite, possessed of a unique, artistic disposition, naturally charismatic, elegant and open.

The topics I planned to cover in our conversations – and had it been possible, there could certainly have been many more – and the complex issues raised I shared with him in advance, so that in his replies he sometimes refers to a question that had not been raised at that point, but was featured in one of my letters. It’s also true that many of the things we discuss arose spontaneously.

Garrick Ohlsson, while talking, illustrates his musical ideas – he sings parts of pieces, plays on the table as if it were a piano. This kind of response I have tried to include in the book by printing musical examples. They are just as much a part of his responses as the words he chooses.

I am grateful to Garrick Ohlsson for his time and his considered responses to my questions. I hope too that I have gone some way towards successfully presenting a faithful portrait of this exceptional pianist.

KAMILA STĘPIEŃ-KUTERA

Garrick Ohlsson would like to express his appreciation to Kamila Stępień-Kutera, whose deep knowledge and perceptiveness shaped the interviews that make up this book, as well as his thanks to Robert Guter for his help with editing the English language edition.

I would like to dedicate my work to the memory of Professor Michał Bristiger, to whom I am forever grateful, and to my husband, Jarek, and my son, Konstanty, without whose support and love none of this would have been possible.

Kamila Stępień-Kutera

A PIANIST’SEDUCATION

The personality of a pianist is influenced by the people around him, and it changes over time. What made you the pianist you are today? How did it start?

I am an only child. Neither my parents nor anybody in my family were musicians.

My mother was born in New York of Sicilian immigrants who came to America by ship in the, when America was the land of dreams for poor Europeans. They achieved very modest success here. Among my Sicilian and Swedish ancestors there were no musicians that I know of, although I was told that my Sicilian grandmother’s grandfather – so, four generations back – was a good country violinist who played at weddings and parties. But I don’t even know his name, so that’s more like a legend from ancient times. I don’t know where we got it, but we had some kind of old upright piano. By the time I was three, I was trying to pick out melodies. My mother even wrote in her diary: ‘Garrick seems to be interested in the piano.’ And she added: ‘Who knows? Maybe someday he will be another Rachmaninov.’ Later, my father was transferred from New York to South Carolina. My parents sold the piano – we didn’t have any instrument and I didn’t think about it at all. I was just a completely average, normal boy, four years old, to five, to six. We came back north when I was six, and I began to go to school. I still wasn’t thinking about music. But when I was eight my parents got a small upright piano because they both – my father in Sweden, where he came from – had piano lessons when they were that age, so they felt it was part of growing up.

My mother took me to the Westchester Conservatory of Music in White Plains, in those days a small, local school. The director was a Russian immigrant. He was tall, with long, silver hair, and he smoked with a cigarette holder, like a character in a Hollywood film. In 1956 he must have been about sixty-five years old. He was trying to be grand and superior to the locals, I suppose. With his deep voice and Russian accent, he seemed scary to me. If the school accepted a child, the parents had to sign an agreement to buy six months of lessons – a guaranteed business deal, very American. Because my mother wasn’t sure if I would be interested enough, she asked: ‘But if he doesn’t like it after a few times, can I take the rest of the lessons?’ The answer was, ‘Of course, no problem.’

My mother did play piano, and she must be where my musical talent comes from. She did not play very well, but her tone was not bad and she could pick out melodies. She had a real, natural feel for music, and she responded to music deeply without having been educated very much. If she heard a singer on the radio or on a recording who had a beautiful voice, she would immediately respond to the beauty of the voice and the music. My father liked music, but it wasn’t the same kind of immediate understanding of what is and is not beautiful, or even what he liked or didn’t like – that strong feeling that musical people have very naturally.

TOMLISHMAN

And so I started lessons with my first teacher, an Englishman from Leeds, Tom Lishman – Tom, not Thomas. I took to piano playing like a fish to water. I just started swimming immediately; I loved it. I was lucky with him because he had two significant qualities: he was good with children – in other words, psychologically, he liked to teach children – but he was also a cultured man. Moreover, he had studied with two important people. First, Frida van Dieren, who was a prominent student of Busoni, an Englishwoman, the wife of the Dutch composer Bernard van Dieren. And second, Tom had also attended master classes with Cortot, who gave plenty of them, I think even in England, but certainly in France, where Tom probably went. Cortot was a little bit like Liszt: when he taught master classes, there were hundreds of people there. Some of them played under his guidance, but above all he was very inspiring and very generous in sharing his experience.

Tom therefore had a deep appreciation of music at a high level. During his stay in London he had the opportunity to attend all sorts of concerts, and he heard the world’s greatest pianists. His combined knowledge and intuition enabled him to recognise a talented student and to develop the talent he heard. I didn’t know all of this – I was just lucky. I loved him. He was very, very good at what he did. I started in September 1956, when the school year began. The lessons proceeded according to a method called John Thompson Piano Studies, divided into years: year one, year two, a progressive, standard way of teaching. By Christmas I had completed the first four years, but I still wasn’t conscious that my progress was faster than average – although I felt it was rather easy for me. But I also had an idea of some difficulties because I was constantly being challenged.

After a few months my teacher signed me up for the Christmastime children’s recital at the conservatory. This conservatory had, I think, about forty students studying there. It was a very small school. But in order to be on the programme, the director had to hear you. It was the first time for me. I didn’t even know what an audition was. I entered the hall, and the director sat at the back. ‘What are you prepared to play?’ he asked. I played Clementi’s First Sonatina:

Example 1. Muzio Clementi, Sonatina in C major, Op. 38 No. 1, bars 1–2, right hand part

After I finished, he didn’t say anything. Tom, my teacher, called me later and said, ‘You’ve been accepted to play at the recital.’ I was excited, though I didn’t know what a recital was. In those days programmes for such concerts were mimeographed. I think the same method was used in Poland – it was cheap, and you could print a lot of copies. So there was a flimsy mimeographed programme, and I was placed at the end, after fifteen or sixteen children. Some were as young as six, many were older, but I was the one who was placed at the end. I had no idea why I had to wait so long for my turn. I sat there and I heard how terribly most of the children played. I suddenly realised, for the first time, that I was different. Those children had wrong notes, bad rhythm, memory, nerves. They would stop in the middle and run crying to their mothers. And I thought, ‘What’s wrong? It’s hard, but it’s not that hard.’ Finally, I played, and the whole audience applauded a great deal. They liked it. I didn’t play one wrong note, and even the director congratulated me. He said, ‘Young man, you didn’t play any wrong notes. Very good, good rhythm, good.’

I didn’t know anything. But that’s when I got the idea that I could play for people. I wasn’t nervous. I was excited. I didn’t know if they liked me, and then I got praised. So that’s a fantastic motivation. And yet it could have been different – even with very talented people it doesn’t always go well during the first time in public, because people bring many different psychological aspects of their life to everything they do. In short, it was my debut. That was the first time I thought, ‘I’m better than most of these kids.’ Nevertheless, I still didn’t know what it actually meant, but I was incredibly enthusiastic and I kept on studying a lot, making very good progress. Every year I played in the children’s recitals, and when I was nine I began to accompany a couple of violinists who studied with a friend of my teacher’s, a South African, one of those very small, older ladies who look a little bit like a beer barrel on two sticks. She had a very high voice, and she would always say: ‘Garrick, stop playing so loud, You can’t hear the violin!’ Well, I was nine years old and very happy to play loud. She wasn’t angry with me – she explained the issues of power and listening, and balance. It was an important lesson: so right from the start I was collaborating with other people. I was continually making a lot of progress, and by the time I was about eleven, we went to Europe one summer to visit my father’s family in Sweden. My mother, who was always very imaginative, said: ‘We’ve come all this way. We have to do something else.’ So we went to Rome for a few days and London for a few days. I had been to Europe when I was two, but I remember nothing of that trip. By the way: one small anecdote about me – I was ‘made in Sweden’. We know exactly where and when.

So you are partly European.

Yes, I suppose I am some kind of European. Anyway, by conception. Since we were stopping in London and Tom Lishman was going to be there, too, he arranged for me to play for his teacher. I think he wanted her blessing, just to sort of say, ‘I think you’ve got a really, really good one there.’ I prepared a programme – Beethoven’s Op. 22 Sonata, Liszt’s Eleventh Hungarian Rhapsody, Chopin’s Nocturne in C-sharp minor, Op. 27 No. 2, and Moszkowski’s Etude in G, not one of the famous ones. Something just to show off brilliance. So, see? Polish composers already. But of course I didn’t know where anybody was from. You don’t know those things when you’re a kid. Frida van Dieren, a very distinguished old lady, heard me and gave Tom the assurance he needed. By the time I was thirteen, I’d been studying with Tom for five years. He was also very inspirational about music in general. It wasn’t only the piano. From him I learned that music is about something much bigger than the piano, much bigger than yourself. It’s about communication. It’s not only piano music but a whole world of music. He introduced me to great choral and chamber music – he played a lot of collaborative music, too. I remember when I was ten, he played, with his South African friend, Bartók’s First Violin Sonata. I had never heard atonal music before. The concert took place in the small conservatory hall. They began, and the violin came in on – as it seemed to me – the completely wrong note. I burst into laughter and my mother had to take me out. I couldn’t believe that something that sounded so wrong – and that I wasn’t permitted to do – was being played by grownup people. ‘Why can’t I do it?’ I revolted.

SASCHAGORODNITZKI.JUILLIARDSCHOOLOF MUSIC

By the time I was thirteen, Tom realised that in order for me to progress, I would need greater challenges than the conservatory in White Plains was giving me. I would need to be with more talented young artists. Somehow, he reached the famous Sascha Gorodnitzki and managed to set up an audition. One Sunday afternoon I went with my parents and Tom to Gorodnitzki’s beautiful apartment on Central Park West, on the fourth floor. It was a huge apartment; the living room alone, overlooking Central Park, with had two Steinway concert grand pianos, with enough space to present concerts for a hundred people. Gorodnitzki was an impressive, good-looking man. I was quite nervous and excited. I had already heard recordings of him playing – and we have to remember that not everybody made recordings in those days. Gorodnitzki wasn’t a superstar, but he was famous enough to command respect, somebody to be reckoned with. I also knew that through his teacher Joseph Lhévinne he was heir to Anton Rubinstein’s style of piano playing. In terms of pedigree, that was additionally impressive.