69,99 zł

Dowiedz się więcej.

- Wydawca: Prószyński i S-ka

- Kategoria: Literatura faktu

- Język: angielski

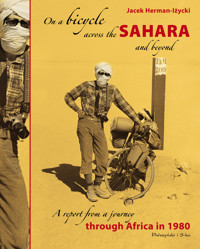

A report from a journey through Africa in 1980.

I travelled for over 28 months –

From 20th of June 1979 until the end of October 1981.

I started with a three month visit to North America.

I hitchhiked from New York, across Canada, all the way past the Arctic Circle, to Taktoyaktuk by the Beaufort Sea, and then to Alaska. I took a flight from Anchorage to Seattle and hitchhiked again from there, across Canada, back to New York.

I returned to Europe but didn’t board the flight destined for Warsaw in Frankfurt. Instead, I hitchhiked to the Netherlands via West Germany, East Germany and Denmark. I spent three months in Rotterdam, preparing for a bicycle journey around Africa.

During the eleven-month long return journey from Africa to Poland, I worked in Greece, Switzerland and the Netherlands.

In Africa, I cycled 10,500 km.

I set off from Algiers and reached Kenya via Algeria, Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Sudan and Uganda.

Additionally, I covered over 4,300 km using public transport and cars while following this route.

On my way back to Cairo from the Kenyan-Ugandan border, I covered about 7,200 km, travelling by truck, train, boat and bus.

Cumulatively, between 9th of January and 2nd of December 1980, I covered over 22,000 km in Africa, using various means of transport.

Jacek Herman-Iżycki

Ebooka przeczytasz w aplikacjach Legimi lub dowolnej aplikacji obsługującej format:

Liczba stron: 585

Podobne

Dedicated to my Mother

Contents

Prologue

Preparations for the journey

Across the desert

The first 2,000 kilometres

800 kilometres of Saharan roadless tracks

The final 400 kilometres of the Sahara

Across the savannah and the equatorial forest

Across the savannah in northern Nigeria

In Northern Cameroon

Yaoundé and the mountains of West Cameroon

Douala and the forests of east Cameroon

On the way to the Central African Republic

Searching for the Pygmies

En route to Sudan

Across southern Sudan and Uganda

The return to Europe via Sudan and Egypt

Epilogue

Prologue

The very first time, the idea of travelling across Africa on a bicycle entered my mind was somewhere on a ship on Lake Nasser, or perhaps on the train from Wadi Halfa to Khartoum. It was most certainly in 1976, during a Warsaw University of Technology Student Globetrotters Club “Maluch” trip to Egypt and Sudan. It was then when I fell for Africa hook, line and sinker, and I desperately wanted to return there. That time around alone and for longer.

Back then I had some ideas about travelling across Africa, but they were pretty vague. Where to go was by no means clear. I believed that everywhere would be interesting. In time, as my travel plans started to crystallise, basic questions kept emerging, and the answers soon followed.

Where to start? As it turned out, the choice fell on wherever it would be cheapest for me to get with my bike.

How long should my journey last? In this regard, I didn’t want to make any assumptions. No limits, depending only on how far my desire, health, stamina, and money would go.

How would I return? This was something I would investigate once I landed there. It depended on how far I would manage to ride. The most likely a scenario was a return journey on a Polish Steamship Company ship with a ticket bought on credit because my plan was to ride until I run out of money. I knew one thing. I had to start somewhere by the sea and, if everything went well, finish the journey in onother seaport. In the end, it almost worked out this way…

How did I manage to organise that journey of mine? What difficulties did I have to overcome? What tricks and practical solutions did I have to use? I tell it all here.

What’s most important to me though was my desire to describe the journey itself as accurately as possible, the journey I made thirty-five years ago. Specifically, its most difficult stage, the ride across the Sahara Desert. Notes I made, which can be described as travel journal, proved to be helpful here. In my notes, there aren’t many impressions of the lands I passed through or descriptions of the people I have met. What I saw was captured better in my photographs. Travel photography was already a passion of mine back then and remains a passion to this day.

The journey begins. 8 January 1980, Breda, the Netherlands

Pages in my passport with visas

Preparations for the journey

Travelling in the times of the Polish People’s Republic

Travelling in the times of communism wasn’t easy. To be able to leave the Polish People’s Republic, one had to endure formal procedures which were not only tedious but often humiliating. Whenever I was setting off, the most troublesome task was always obtaining a passport and the necessary visas. Someone may ask “What about money?”. Sure enough, money had to be earned. Earning money was a lot harder in communist times than it is nowadays. It was nearly impossible to earn enough for such a long journey whilst working in the Polish People’s Republic. The black market and the in-exchangeable Polish currency, the Polish zloty, meant that the monthly Polish income was less than a day’s pay in the West. Thus, my first trip was the only one I funded by my work in the Polish People’s Republic. I worked until I had just barely enough for a passport, which I acquired with the help of friends who had emigrated and sold me US dollars at a significantly discounted rate. I deposited one hundred US dollars in a so-called “Account A” (Foreign Assets bank account) of the Polish Savings Fund Bank of Poland. I was now eligible to apply for a passport. With a passport in my pocket, I was ready to start earning money abroad.

The very first time I travelled abroad to the West was in 1974, after completing my third year as a student at the Warsaw University of Technology. As a rule of thumb, students’ holiday passport applications were rarely denied. For this reason, leaving the country while still a student was the safest bet. I was due to finish my studies at the Warsaw University of Technology within a year. One year, I thought, was a bit too short to thoroughly prepare for the journey ahead. I needed to buy myself some more time as a student.

After graduating, I passed an exam and was accepted as a postgraduate student for a two-year course at the African Institute of the University of Warsaw. Killing two birds with one stone, I retained my student status and gained valuable time to prepare for the expedition…

Through my studies, I was also able to learn more about Africa. Languages were the priority. I more or less knew English already. French was the language I concentrated my efforts on as it was absolutely invaluable in Africa, and I only knew the basics at the time. Languages were never my forte, I knew this since childhood. It has always been something of an Achilles’ heel of mine.

During my African Studies, I learnt not only French but also Arabic, which I hoped would help me during the North African leg of my journey. As you may know, Arabic is a notoriously difficult language and, regretfully, my studies it didn’t have a lasting impact. However, even the very basic phrases I did learn proved to be enough to pique the curiosity of the local Arabs and win their sympathy. In Algeria and Niger practically everyone spoke French. It wasn’t as simple in Sudan though, where few people spoke English. At markets and in villages I often had to revert to gestures as a way of communication or dig into my ever so small collection of Arabic phrases. My knowledge of Arabic numerals, in speech and in writing, proved an invaluable asset.

Upon my return from Sudan in October 1976, during my final year as a student of Polygraphy, I planned to complete my Warsaw University of Technology studies in 1977 and my Postgraduate African studies at the University of Warsaw in June 1979. Immediately after, I’d embark on my journey. My plan almost went smoothly, but not quite as I wanted it to.

I had planned a trip to Canada for 1978. The plan failed as I was denied a Canadian visa. The Home Secretary of the Canadian Servas, an international peace organisation, stepped in and attempted to get me the visa I needed. To his annoyance, the visa was denied once again, and it was only after he appealed the decision, the matter was resolved in my favour. Thanks to his efforts I was granted a Canadian visa in September. This meant it was already too late to go as the start of the new academic year was looming over my head. Under no circumstances did I want to even consider abandoning the idea of my Canadian trip as to me it was a once in a lifetime opportunity.

Fortunately, the Canadian visa was valid for one year which meant I could go there in the summer of 1979. However, this meant I had to postpone my African trip. The Polish People’s Republic passports were valid for one round trip only and had to be returned and exchanged for a Polish People’s Republic identity card strictly within a week of returning. For this reason, I had no choice but to complete the African journey later but still as part of the same trip I started by leaving the Polish People’s Republic for Canada.

Had I returned to the Polish People’s Republic after visiting Canada, there’d have been no chance of me being issued with a passport for the second time in the same calendar year. And so, I knew my African journey would have to start elsewhere and certainly not in Poland. I could of course apply for a passport again the following year, no longer as a student but as a fully-fledged engineer with a communist work assignment and a rather modest holiday leave allowance. Therefore, the option of travelling by ship to Africa from Poland had to be discarded.

Two choices were left. To travel by land and ferry (from Sicily to Tunis or from Marseille to Algiers – the option to travel from Spain to Morocco would not work as back then it was not possible to travel anywhere from Morocco due to a closed border with Algeria and an ongoing war with the Polisario Front in the south) or to travel by plane. As it turned out, the cheapest option was to fly as plane travel would make all the European travel expenses redundant: the visas, overnight accommodation, food…

Summer, with its high temperatures, was out of the question as my plan was to begin the journey in North Africa. The best seasons were therefore autumn or the beginning of winter, in which case flying was the best option. Since I would be starting the African journey in the winter, there was nothing stopping me from using my already approved Canadian visa in the summer. At the start of 1979, Pan Am airline started to fly to Poland. The company was offering return flights from Warsaw to New York priced at thirteen thousand Polish zloty. And it was possible to buy ticket in Polish currency! With official rate the ticket was valued about $450. At the same time one US dollar was worth about one hundred and thirty Polish zloty at the Polish black market. The black-market value of the dollar was four-and-a-half times higher than the official exchange rate however it was possible to pay for the plane ticket in Polish zloty and it was like buying hard currency at official rate which was no possible in the bank! And so it happened that a plane ticket worth between four and five hundred United States dollars would cost me a hundred dollars... This way, my road to Africa took me through New York and Canada which was absurd only on the surface. Sure enough, I wasn’t the first one. Why, Christopher Columbus on his way to India ended up in America.

When it came to passport issues, help came from the unexpected direction of an American student I randomly met in Warsaw. He provided me with a fictitious three-month invitation to visit the USA. My passport application for the USA trip resulted in a meeting with a “sad man” who warned me, just in case of course, about certain dangerous contacts in America. His advice was to keep my eyes wide open and to give him a call on his direct number upon my return to provide him with a report about my stay in the USA. It goes without saying that I couldn’t disclose any of the true details of the trip to my esteemed interlocutor by admitting that the USA was just a transit point on my way to Canada, which I’d be exploring as a hitchhiker, and North America was just another pit stop on my way to Africa.

In this slightly roundabout way, I hoped to reach the ultimate and most important goal of my entire journey: Africa. There was also no way I could’ve mentioned that my stay abroad would be a little bit longer than three months…

When I finally returned to my home country in October 1981, after twenty-eight months of absence, I did try (just once!) to call the official I mentioned previously, but there was no answer on the number he had given me. I didn’t have a clue whether this man even still worked there, and if so, I’m quite sure he would not have had the time nor the desire to listen to my stories about how hot African weather was. At the time, the political atmosphere in the Polish People’s Republic was also heating up, it was quite clear there were changes ahead…A few weeks after my return, martial law was imposed.

Did it have to be this complicated?

The PanAm airlines flight from Warsaw to New York had a stopover in Frankfurt-am-Main, where I changed planes, swapping a small Boeing for a large jumbo jet! This experience on its own was worth the choice of route I had made.

But the most critical point of the journey was the stopover on the way back from the US. I certainly couldn’t fly back to the Polish People’s Republic, because my passport would have expired the minute I returned. Thus, an understandable nervous tension overshadowed my New York to Warsaw flight check-in. How on earth would I explain to the lady at the check-in desk that, while my luggage was only flying to Frankfurt, I would be continuing all the way to Warsaw?

Thanks to the help of Lidia Tabor, a retired PanAm employee and a Servas activist, everything went smoothly. My plane destined for the Polish People’s Republic hadn’t even left the Frankfurt airport tarmac yet, and I was already standing by the airport exit with my luggage, trying to catch a ride to West Berlin. This part of my plan was of major importance. From West Berlin, I was able to reach East Berlin, where my brother and I had arranged to meet and exchange my luggage.

I gave him my rolls of film and souvenirs. In exchange, he handed me all the essential things for my African journey that I had prepared before leaving the Polish People’s Republic. These included the indispensable Polish instant soups, not only cheaper but also better tasting than the foreign ones! Back then, everything that was made in Poland was ten times cheaper than in the West. I also took some bicycle spare parts and, most importantly, THE POSTERS!

Polish Poster School becomes my pass to Africa

Posters were my way of earning money in the West. For quite a few years I had been funding all my travels by selling Polish theatre, jazz, and film posters abroad. I would sell them in student halls, in the streets, sometimes in galleries or antique shops. I would buy these posters in Polish poster shops or directly from theatres. Their prices varied. Typically, considering the black-market value of the US dollar, they would cost me between thirty to fifty cents to buy. I would sell them all at the same price: two to three dollars initially, then four to five dollars apiece.

The sale of posters would cover my essential travel expenses and bring in money which helped to fund my journeys.

It was mainly young people who’d buy my posters to decorate the walls of their rooms with. Polish posters created during the starlight years of the Polish Poster School were very attractive and different to the ones available in Copenhagen or Amsterdam. I had very hospitable acquaintances in Denmark and the Netherlands, and it was only thanks to their generosity that my travels were possible. If I were to pay for even the cheapest motel or hostel out of my own pocket, I’d never have been able to save enough to travel…

Polish posters proved to be a huge hit with the young people in the West

From Berlin I headed to Denmark, and then to the Netherlands. There, in Rotterdam, I had the use of a small apartment belonging to a friend of mine, who at the time lived in Breda with his wife. I spent October in Denmark; November and December in the Netherlands. This was a very busy time for my poster sales, the same posters which my brother delivered to Berlin and later also send by post to friends of mine in the Netherlands. Thanks to the hundreads of them I had sold, I was able to prepare the bicycle, book a flight from Brussels to Algiers and board it with a nice kitty bank of almost a thousand US dollars in my pocket.

Inspired by an eccentric Englishman

In 1976, the British Globetrotters’ Club bulletin “Globe” published an article by Victor Cannon who cycled across the Sahara Desert on a bike. When a friend of mine from Rotterdam and a member of this club, Jan Krzeminski, learnt about my cycling plans, he immediately put me in touch with this English guy. We met in Warsaw. By sheer coincidence, this eccentric Englishman, an artist, painter, competitive cyclist specialising in time trials, and a cycling traveller, was exploring his matrimonial prospects involving a woman from Warsaw he had met. The marriage deed was successfully signed, sealed and delivered but their relationship wasn’t a happy one and didn’t last long. In the end, the main beneficiary of the Englishman’s Polish love affair was….me.

After a few conversations with Victor in Warsaw in 1978 and 1979, my plans for the African journey started to take shape. I already knew that I would like to start in Algiers and travel as far south as possible. It didn’t occur to me earlier to make a plan, because how can a sane person plan for their solo cycle ride across the Sahara Desert? The Sahara I’d gotten to know by looking out of the train window when travelling through Egypt and Sudan somehow didn’t encourage such endeavours.

Victor Cannon in an oasis in Ghardaïa

I must admit that I briefly entertained the idea of cycling along the river Nile, however, after my talks with Victor, the idea was abandoned for good. Cycling alone across Egypt was not safe, I learnt from Victor, because apparently “people throw stones”. Such a reason might have seemed funny, until I remembered a news report, I’d read earlier about a lorry which had been “stoned”. And of course it’s a lot easier to escape such an attack in a lorry…

Cycling along Lake Nasser, south of Aswan, wasn’t possible either. The route to Sudan along the Red Sea coast was inaccessible too, as it led through uninhabited areas and military zones. Even if I were granted a permit to cross, I wouldn’t be able to cycle this route due to lack of drinking water sources. Entry to Sudan from Egypt was only possible by taking a ferry from Aswan to Wadi Halfa. I had taken this route a few years earlier.

The crossing from Morocco to Mauritania at that time was impossible due to the conflict between Morocco and the Polisario Front rebels fighting for the independence of Western Sahara. Therefore, the only possible land route South lead through Algeria, with Victor reassuring me that the passage through Tamanrasset (now known as Tamanghasset ) was OK and he himself conquered it twice! He had also provided me with some invaluable advice. So, I was following in Victor’s footsteps!

Victor’s advice

Victor made me realise one thing: during such a difficult expedition, a super sturdy bike was a must. Since I couldn’t buy such a bike, he advised I should build it myself. The most important part of the bike is always the frame. It had to be a lot sturdier than a standard one, with the rear luggage rack preferably built as an integral part of the frame. Victor didn’t have to convince me too hard to listen to his advice. Although at that point I had never cycled in Africa, Polish and European roads taught me more than enough. Momentarily, I had a series of flashbacks: to the frame of my Polish “Maraton” bike, which got bent after I rode over a stone, or having to look for a welding my iron luggage rack in Spain in 1974, when it failed to withstand the rigours of Castilian roads, even though they were paved.

While I was able to cope in Europe, such surprises would certainly not be welcome in Africa. Buying a new frame or welding the rear bike rack would be out of the question while cycling in Sahara. Such mechanical failures could potentially wreck my plans. Victor also advised that the geometry of the frame should differ from the geometry of a standard bicycle. What he meant was, the pedals should be positioned higher above the ground. This would make cycling on uneven, rocky roads and tackling stones, potholes or washboard roads easier. This, however, was a lot easier said than done.

In England at the time, there were plenty of bicycle workshops which made frames to order. Most of these were made using “Reynolds” components which were durable yet light at the same time. The era of mountain bikes, invented in California in 1980, was yet to come. Super-sturdy yet light frames, wheels with wide tires designed for bicycles with gears, no one had even heard of such wonders in the 1970s.

Victor walked for two weeks, pushing his bike with a broken derailleur all the way to Tam

Victor’s reaction to my comment that a trip to England to order a frame was out of the question was quite unexpected. As he wasn’t planning on visiting any deserts anytime soon, he would gladly lend me his own bike frame. Although one shouldn’t look a gift horse in the mouth, in my opinion that frame, apart from all the advantages, had one major flaw. Its forks were too narrow to install wheels with wide tyres. In the end though, the advantages outweighed the flaws. Made with Reynolds components, the frame was very durable indeed, had an integral rear rack and the bracket was raised, in line with Victor’s preference. He also threw in the curled handlebars known as “rams”, and a pair of Karrimor rear panniers.

Victor, not only a globetrotter but also an athlete, was adamant about the superiority of thin tyres and racing handlebars. These thin tyres gave me many headaches later on, in difficult terrain. Following Victor’s advice, I installed a forty-spoke rear rim instead of the traditional thirty-six. I was given the appropriate hub as a gift. I bought the best rims by Weinmann, and strong spokes, the thickest available on the market. The front hub, also provided by Victor, was a traditional one, suitable for thirty-six spokes. I bought new wheel bearings, axles, Shimano gears, a Suntour cassette sprocket (freewheel) from twenty-one to thirty-four teeth and thirty-nine and forty-eight teeth sprockets in front.

Victor at a campsite near Agadez in Niger

These gears were certainly not suitable for racing. It would be difficult to cycle faster than thirty kilometres per hour. High speeds, especially when a bike is heavily loaded, could be dangerous. Every pothole is capable of breaking the wheel rim. Back then, gears designed for slow cycling on a bad road surface and uphill were considered extraordinary. In the Polish People’s Republic, I would be able to buy a forty-two sprocket for the front and twenty-seven for the back which would result in a gear setting 1:1,56. I had thirty-nine at the front and thirty-four at the back. So the minimum gear setting was 1:1,15 which worked great. I could easily cycle at a speed of one-and-a-half to two kilometres per hour, which proved invaluable on a steep incline. In truth, I would tackle the incline at walking speed, but I didn’t need to dismount, which allowed me to stick to my cycling rhythm. Today, every geared bike has even better parameters. Victor brought the frame and the other parts to Rotterdam, where I was finishing my preparations. The saddle, front rack, front panniers, the handlebar bag and other missing parts I also bought in Rotterdam.

Victor on a trail. Photograph taken on 20th February 1976 by an Italian camping next to the trail

Victor’s bicycle in the desert to the south of Tam (small photo insert: a break in an Algerian oasis)

The last stage of the preparations

My Dutch visa expired quickly. By December, I was visa-less. It caused me a bit of stress, especially when hitchhiking to Brussels to collect the African visas. Even though I was never subjected to any border controls, the Eastern European feeling of anxiousness and fear remained.

I needed visas to Algeria, Niger, Nigeria, and Cameroon for a start. I didn’t have a clue what would happen later. The vast majority of the other mandatory visas would expire anyway if I applied for them too soon. Only some were valid for six months. This was the case with the Sudanese visa with expiry date in May. However, having been previously granted a visa proved very helpful when applying for a renewal, which I did three months later in the Sudanese Embassy in Bangui, in the Central African Republic. Zaire visa could only be issued in my home country, the Polish People’s Republic. Back then, I wasn’t even aware of this rule. Even if I had been, I wouldn’t have wanted to take the risk: what answer could I’ve possibly given when asked at the Okecie Polish Airport: “What do you need a Zaire visa for if you’re travelling to the USA?”

Instead, after a brief conversation at the Cameroon Embassy in The Hague, a very pleasant lady Consul issued me with a three-month visa. In this case I was actually very lucky. It transpired that, in Africa, the Cameroonian authorities only issue one-month visas which cannot be extended. Hence, I was able to cycle around Cameroon for two and a half months without a care in the world.

I managed to get my hands on visas to enter Algeria and Niger in Brussels, without any problems. The only visa the authorities didn’t want to provide me with was the Nigerian one. It could only be issued in the Polish People’s Republic or in a country neighbouring Nigeria. As soon as the authorities heard I was heading to Algeria, they instructed me to visit a local Embassy.

Why such a journey?

After my return, when presenting slides from my journey, people would ask why I went there in the first place. What was all this effort for, why did I choose to put myself in such a precarious situation? What did I want to achieve? It was difficult for me to answer such questions. I didn’t have a specific goal in mind. I wanted an adventure. The grey reality of my communist country bored me to death. I wasn’t in a rush to live a “grown up” life either. My passion for Polygraphic studies quickly fizzled out and the prospect of working at a printer’s didn’t seem attractive to me anymore.

No girl fancied me enough to want to make me stay, or perhaps the African bug got me so bad that girls just couldn’t compete? Perhaps I wanted to test myself? If so, I wasn’t even aware of it back then. Now, I think that the wish to overcome my weaknesses, to prove to myself that I could do it was present in me. I remember that, after a few months on the road, I already knew this was by far the most amazing journey of my life. This realisation was swiftly followed by fear that this adventure would one day come to an end and then what…?

By mid-December, I felt I was almost ready to go. The only thing that remained was to buy a plane ticket, using my student discount of course. I had my eye on a Sabena deal, a Brussels – Algiers flight for 200 Dutch guilder. In the end, I decided to spend Christmas in the Netherlands and head out in the beginning of January. I left Rotterdam fully packed and cycled to Breda, where I stayed overnight at a friend’s place. The next morning, I headed to Brussels. After a night at a youth hostel, I took the metro to the airport. From there, my bike and I departed for Algiers.

And just like that, on the 9th of January 1980 at 14:30 local time, I landed in Africa. It marked the start of a journey the end of which was uncertain to me in terms of both place and time.

Choice of route across the Sahara Desert

The route I chose was quite popular back then. It was used by those travelling in 4WDs, as well as locals whose most popular choice of vehicle was lorries. But for a cyclist, this route was certainly an unusual one. Back then, I’d not heard of any other Polish person who cycled the entire Sahara Desert from north to south, solo, on a bike. That said, I’m aware of some of the spectacular achievements of contemporary cyclists and, I think, a few of them conquered the Morocco and Mauritania route.

Do their journeys compare to mine? It’s hard to say because I’m unaware of any reports from such travels. These cyclists could probably say more on the subject if they flicked through the notes from my journey. Fifty years earlier, and in completely different political circumstances, Kazimierz Nowak attempted to cycle across the Sahara Desert. He set off from Libya in 1931 but, after dramatic adventures, he had to turn back and eventually reached the Black Land using a route which followed the Nile. His story had been known before the World War II thanks to his reports published in the press. In the 1960s, a book with his photographs from Africa was published (“Przez Czarny Ląd“(Across the Black Land), Kazimierz Nowak, Elżbieta Nowak-Gliszewska, Wiedza Powszechna, 1962). The book however was about Africa, the place, not about his journey. Even though I read this book as a child, and it contained a small map of his route, it was not an inspiration for my journey.

I only read Kazimierz Nowak’s press articles after my return to the Polish People’s Republic in the early 1980s, in the archived issues of the magazine “Na Szerokim Świecie” (In the wide world)”. I came to know the details of his journey by reading “Rowerem i pieszo przez Czarny Ląd. Listy z podróży odbytej w latach 1931–1936” (By bike and by foot through the Black Land. Letters from the journey made between 1931–1936), Kazimierz Nowak (complied by Lukasz J. Wierzbicki, Sorus, Poznan 2000).

Victor’s watercolour – a Christmas greetings card, 1984

Water in the Sahara Desert

The route across the Sahara led from Algiers, the capital of Algeria, located on the Mediterranean coast, through Tamanrasset (Tamanghasset) and Agadez to Zinder in Niger. This route’s total length is 3300 km, 800 km of which are roadless tracks from Tamanrasset to In-Gall. This part of my journey was especially difficult and required very particular preparation. The first and longest stage to In Guezzam (Ajn Kazzam) was 400 km. There wasn’t a single oasis with a drinking water source along the way. The next stages were: 30 km to Assamaka, 170 km to In-Abangharit, 88 km to Tegguiada in Tessoum and 88 km to In-Gall. These were the only oases which had drinking water. I was working on the principle that I’d be able to cycle roughly 40 km a day, so for the longest stage I needed a supply of water lasting ten days, which equalled to approximately fifty litres. It was impossible to carry so much water on the bike. Taking a small trailer would slow me down to such an extent that I wouldn’t be able to stick to my plan of cycling 40 km a day. This would mean I’d need even more water. This plan wouldn’t have worked.

It became clear to me that, when it came to water supply, completing this stage, including the Sahara Desert, without some help from the passing vehicles would be impossible. The maximum amount of water I could carry was nine litres which would initially last two days. Later, due to higher temperatures, the same amount would only last a day-and-a-half. I kept topping up my drinking water supply. Tourists, local oases’ residents and, at times Arab lorry drivers would help me along the way.

Food

I tried to be a lot more independent with my food supplies. Based on Victor’s advice and experience, I had prepared rations for twenty morning and twenty evening meals. During the day, water with glucose, sweets and dates were supposed to sustain me. Basic rations consisted of instant soups, which were supposed to be combined with pasta, bread or rice. Breakfasts would be mainly milk-based, prepared using powdered milk. The size of the portions was based on how much I ate while approaching Tamanrasset (Tamanghasset)on a tarmac road. I was able to complete the trip from “Tam”, as Tamanrasset was called for short, to In-Gall within twenty days. My calculations proved precise. Establishing the size of the portions, however, was more complicated. I couldn’t get my hands on enough pasta in Tam. I got the very last packet from the shop. I couldn’t buy as much bread as I wanted either, and the rice was of poor quality. It needed to be boiled for a long time, so I abandoned the idea of buying a larger amount.

Underestimating my nutritional needs in such a changing environment, in particular not taking enough care to provide my body with sufficient calories, was a significant mistake. 200 km cycled on tarmac required a lot less energy than pushing my bike through the sand. The constant getting on and off the bike, getting stuck in the sand, or even a very slow cycle along a sandy piste (fr. piste – a well-used trail across a desert, lit. a path) would really leave me drained.

The food rations I’d prepared turned out to be too small for my needs. If not for couple of the gifts and snacks received from tourists, and the dates purchased for me in the last oasis in In Guezzam in Algeria, I probably would not have managed this route.

Travel equipment

I took camping equipment from Poland. My nylon tent “Mikrus” did not have an inner tent and was not suitable for heavy rain but was just right for the desert. Initially, the down sleeping bag was indispensable during frosty desert nights. Later I could have used a thinner one, but I got used to sleeping in just the second, silk sleeping bag which I used as a sheet. Victor would cook over a fire which he made every evening. He mentioned that on some days he’d be collecting sticks throughout the day. In his opinion, a camping stove was an unnecessary ballast, as one should have as little luggage as possible. Theoretically, he was right. Although I thought that the energy spent to collect the wood for the fire was greater than that required to carry a stove. I was very attached to my German Democratic Republic made “Juwel” and there was simply no way I’d leave without a petrol stove. One can get petrol everywhere, even in the equatorial forests where main mode of transport are still pirogues, but no one rows anymore, instead people use detachable engines.

A set of two canteens, a handle, frying pan/lid, 500 ml mug and a cup from a PanAm aircraft was all the kitchenware I had. I didn’t carry a kettle. Based on the British tea-drinking tradition, a kettle was something absolutely indispensable when travelling. I had a different opinion on the matter. My approach was more practical, and I made do with a simple canteen.

Victor’s watercolour – Christmas greetings card, 1986

First Aid kit and vaccinations

I was starting my journey in good health, and I did not take along any special medication. My only complaint was my spine and pain in my back caused by its curvature, but there’s no medicine for this condition. The only medication I needed were those used to treat common travel illnesses. To treat common colds and flu-like symptoms I had Calcipiryn, as well as a type of strong antibiotic I intended to use, should the Calcipiryn fail. An antibiotic would come in handy for a more serious illness, in the absence of professional medical care. For cases of food poisoning, I had charcoal tablets and sulphaguanidine, and for toothache I had Gardan. I packed dressings and plasters for small cuts, as well as a bottle of Gentiana as a disinfectant. A tube of Sudocrem proved very useful. This antiseptic ointment heals all grazes and skin inflammations as fast as lightning. I had an elastic bandage in case of a more serious injury and chlorine tablets to disinfect the drinking water. A jar of Arechin was supposed to keep malaria away.

A little yellow book confirming a vaccination against yellow fever was mandatory. Without it, I wouldn’t be able to enter most African countries. My vaccination dating back to 1976, from my previous visit to Africa, was valid for ten years but I had to renew my cholera and smallpox vaccinations. The smallpox jab was only valid for three years and the cholera one for six months, so I chose to get vaccinated again in December, in Rotterdam. Another vaccination I chose to get was tetanus. My First Aid kit also contained a mosquito repellent which I had bought in the Netherlands. It had a DEET formula, which was believed to be the most effective one on the market.

My funds

I touched down in Algiers with 230 Deutsche Marks, 800 French Francs and 100 US Dollars in cash, as well as 800 Deutsche Marks and 400 French Francs in Travellers Cheques. Considering the exchange rates, all this money equalled to 950 US Dollars. I received a gift of 135 Nigerian Naira ($170) from Polish people working in Zaria (Nigeria) and 9000 CFA Francs ($45) from the employees of the Polish Factory of Paper Machines “Fampa” from Cieplice who at the time were installing one of their machines in Edea, Cameroon.

In the Central African Republic, I sold my shaving razor for 1500 Shillings ($7.5) and in Sudan I traded in my “Zenit” camera for 45 Pounds ($55). In Uganda I was also given 1100 Shillings ($20) “for the road” by a Polish guy I stayed with in Kampala.

When I was down and out in Cairo, right at the end of the African stage of my journey, I met a Swiss guy of Polish origin and borrowed $50 from him. I used the money to buy a plane ticket to Athens, where I landed with nothing but 20 Deutsche Marks in my pocket. During my eleven months in Africa, I spent almost $1300. If we take away the $50, I spent on the ticket to Athens and $10 (20 Deutsche Marks) I had left, my daily expenses equalled to $3.5 per day.

Bicycle, tools and spare parts

It was very important to take all the relevant tools and spare bike parts. The success of the journey depended heavily on them. While it wasn’t difficult to get a set of bicycle keys in the Netherlands, one could only dream of getting such things in Africa. In my kit, I had three bike keys which were totally new to me. Polish bike chains were typically linked using a split cotter, but I had a classic, five-speed chain which was thin and didn’t have a cotter. All I needed to take it apart was a small chain key used to remove the pin. This solution was entirely new to me. The second specialist key was used to take the crank set off the crank axle. Polish bicycles had a crank key which would often come loose and could be removed by simply hitting it with a hammer or even a rock. But my bike was equipped with a different mount: a groove technology. Without a special key, I’d sooner bend the cranks with a hammer than actually remove them.

I never used this particular key as I didn’t think that the axle needed lubricant. Putting the parts back together without the required precision, too loosely or too tightly, which was not unlikely in in rough terrain, could cause the bearings to wear down quickly. I also had a third special key for unscrewing the cassette from the hub. This one came in handy in Cameroon when I was changing the rim and hub, but it died in the Central African Republic. After six months and 6000 km of cycling, the 5-speed cassette was so worn down that it started to give and cycling was out of the question. So, I had to change it. All attempts to remove the old one with the special key failed miserably. I finally removed it by welding a half-metre long iron bar to the cassette. Luckily, the hub survived this intervention.

A pair of small pliers and a pair of scissors supplemented my bike key kit.

In terms of spare parts, I carried a full rear derailleur, chain tensioners, a set of brake and gear cables, spokes, a rim and three tubes, not to mention a sizeable supply of glue and rubber patches for the tubes…The bike repair kit I took with me was well thought through. The only things missing were short spokes for the rear wheel, a clear mistake, and then the five-speed cassette but luckily this didn’t cause me too many issues. The bigger mistake was taking just one spare tyre. I clearly needed two spares, and this fact caused me a lot of grief, especially towards the end of the Sahara trek and the subsequent stages of my journey.

Wheels equipped with wider and thicker tyres would have been a better choice for sure. Yoko, a Japanese guy I cycled with for a while, had such tyres. He didn’t suffer from tube punctures as often as I did.

Interestingly, I did actually ask my brother for two spare tyres. I wanted them to be sent to the Polish People’s Republic Embassy in Lagos, Nigeria. Sending anything at all to Nigeria was a mad idea to begin with. As it later turned out, an even more mad idea was attempting to use the Embassy’s address for this purpose. The idea of sending a parcel in my name, but with the Embassy’s official address on the package truly puzzled the Embassy staff. Nothing ever arrived, and I never received the parcel. So, I was very surprised when, after two years, the parcel containing the spare tyres turned up at my brother’s address, marked as a “Return”!!!

Across the desert

The first 2,000 kilometres

Algiers welcomed me with a mixture of snow and rain. Even though this was Africa, the southern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, it was as cold as in the Netherlands! At the airport, after landing, I was so excited and so nervous that I punctured the tube while inflating one of the tyres. My journey was off to a great start: I had to change the tube in my tyre. What a great start indeed! In the end though, this initial bad luck turned out to be beneficial. By the time I had gathered myself, all the other passengers had left. At the passport control, no one asked me any questions. I managed to cross the border without the mandatory exchange of $100. I knew that the black market would give me a far better exchange rate. This gave me a head-start at the very beginning of my journey. In town, I exchanged French Francs to Dinars at 1:1 rate, which was a bit better than that offered by the banks: 1 Frank to 0,89 Dinar (D). Later I managed to find an even better rate of 1:1,2. The distance from the airport to the city centre of Algiers was about 20 km. I started looking for a hotel. This was not easy. As it turned out, all the rooms had been taken. It was only with the help of two students, one of which spoke English, that I managed to find a room in Hotel Biarritz, 18 Rue Debbib Chérif. It set me back 17 D which was quite expensive, but I didn’t have a choice.

Djama’a al Djedid, “New Mosque” in Algiers, known as “Mosque of the Fisheries’”, erected by the Turks in 1660

10.01, Thursday

I decided to visit the Polish People’s Republic Embassy in the morning. My passport was going to expire in May, in about four months’ time.

The Embassy welcomed me with a cold shower: they were unable to help. My only option was to write to Warsaw and wait three to four weeks for a reply. Instead of a passport, I receive a second insert for 3 D plus 28 D administrative fee. A contact obtained from some acquaintances of mine proved equally useless: just a name without an address, a person no one had any knowledge of in Algiers. The rain kept pouring down. After this visit I felt awful. I went back to the hotel and slept for fifteen hours.

View of the contemporary buildings by the boulevard in the centre of Algiers

11.01, Friday

I located the Embassy of Nigeria. It was Friday, why was it closed? I had completely forgotten that I was in a Muslim country where Fridays are treated like our Sundays. The Embassy was supposed to re-open on Saturday. I wandered around town for a bit and met two French guys looking for a place for the night. I suggested my hotel and showed them the way. Happily, they paid for my couscous dinner. Life was not that bad. I ate a baguette with orange marmalade for supper. The baguette was 0.6 D, a five-hundred-gram tin of marmalade 3.5 D. Survivable prices. Slowly but surely, I got used to the thought that I was in Africa on my own and I could only count on myself.

12.01, Saturday

Nice chat at the Nigerian Embassy. My visa would be ready on Monday. We discussed cycling around Nigeria. They discouraged me from visiting the south of the country as it was dangerous, but the north, where I was heading, was safe and the roads were decent.

My mood much improved, I now started looking for the Embassy of the Central African Republic (CAR). It took me three hours to find the right district, then the correct street, only to be informed that the Embassy had been relocated to a new address four years ago. The local police station finally provided me with the new address but by that time it was already too late to visit. I looked for hosts from Servas in the hope that they would offer me a room for the night or at least help me find the Embassy of the Central African Republic. As it turned out, the hosts lived somewhere on the outskirts of the city. I cycled for over 30 km to reach them, all in vain. Their helpful neighbours informed me that the hosts had left for France. All these kilometres in the city, in the rain, up – and downhill proved to be an excellent preparation for the journey into the interior of this country.

Algerian kasbah close to my hotel

13.01, Sunday

I made my way to the Embassy of the Central African Republic but “ils sont partis” (they moved out). I go back to the Polish People’s Republic Embassy and asked them to forward the permit to extend my passport to the Polish People’s Republic Embassy in Nigeria. Finally, I received an address of a friend of a friend from Warsaw. She lives in the outskirts, in Cité Bougara. When I turned up on her doorstep but there was no-one. This way I had cycled another 40 km just for kicks. I felt that I had earned a proper dinner: soup 3 D and couscous 4.5 D. This was an extravaganza, the day before I had only had soup for 2.5 D. As I was having dinner, I made a decision: I would head out the next day!

By now, I could find my way in Algiers alright. This was the second day without rain, so I spent all afternoon sightseeing. This city is cruel to cyclists, as every new district means another uphill cycle, which is totally worth it though for the views. The seaside boulevard with its impressive façade of French colonial townhouses left a lasting impression on me. Later that evening, I rode back through the meanders of “kasbah”, the old town. This time I found my hotel easily.

Algerian kasbah – old town on a hill erected during the Turkish reign.

14.01, Monday

I was granted a one-month Nigerian visa which expired on April 14th. I hoped that I had managed to enter Nigeria by then. At least this Embassy did not skin you alive, financially speaking. The cost of my visa was only 16 D. I left my hotel at eleven o’clock. This wasn’t the best start, as my knee hurt. The pain got pretty bad during steep inclines.

A Muslim woman in a traditional outfit

In addition, before departing, I had to fix a punctured tube.

It was 50 km to Blida, my initial goal. After 10 km, the city landscape disappeared without a trace. I was now cycling through orange groves and farmland. A few kilometres from Blida, the mountains started to appear in the distance.

I got another puncture, my second that day, this time it was the rear wheel. A rear tyre puncture always causes more hassle than the front tyre. You have to remove all the luggage, take the wheel off, while dirtying your hands with chain lube in the process, take the tyre off, change the tube, inflate it and put the wheel back on. It took me about fifteen minutes. I was getting a lot quicker. I decided against cycling into the city. I ate soup and some pasta for 8 D. I passed Oran junction and headed in the direction of Médéa (Al-Madiya). I stopped to sleep 10 km past Blida. I found a small path leading away from the main road. I followed it and, by five-thirty, I was setting up my “Mikrus” tent. I managed to squeeze the whole bike plus luggage into the tent, with room to spare for me.

My Nigerian visa

15.01, Tuesday

The morning was rainy. I didn’t get up until eight o’clock. It was a struggle to endure fourteen hours in the tent. At this point in my journey, I was not yet tired, the climbing was just about to start. I had the previous day’s sandwich for breakfast. The drizzle continued but I had to get the show on the road…

TEMPERATURES

It’s worth remembering that I crossed the Sahara Desert in the winter. Initially, I was bothered by snow, frost, and cold wind but the further south I cycled, the more pleasant the weather became.

High temperatures started to bother me only after I had cycled for approximately 2000 km. I can’t be precise as I didn’t take any temperature readings, but it may have been thirty degrees Celsius in the shade to the south of Tamanrasset (Tamanghasset). The further south, the hotter it would get. It had nothing to do with the proximity of the Equator. Realistically, temperatures in the Equatorial Zone are not overly high. It’s near the Tropic of Cancer where the temperatures soar. I crossed the Tropic prior to reaching Tamanrasset (Tamanghasset). Towards the end of February, it kept getting hotter. March would bring heatwaves. Towards the end of my cycle ride across the Sahara, the temperatures would reach up to thirty-five degrees Celsius in the shade. The way I estimated it was by comparison with Zinder, where I arrived a month later, and the temperature would reach forty degrees Celsius. Things would become a lot more difficult at that point. I remember being stubborn and cycling during the day for a while, which resulted in a slight sunstroke. Unbearable heat would bring me to my knees. As I was later told, it was forty-two degrees Celsius in the shade. However, cycling in very high temperatures when you can hide in the shade is something quite different to cycling through an open landscape, without a trace of shade in sight. The shady spots where I could hide during the day were very few and far between, which made them priceless!

I bypassed Médéa . I had a large meat sandwich at the crossroads. Expensive, 7.5 D, but I was very hungry and needed to tackle a considerable ascent to a town called Berrouaghia (Birwaghia), uphill for 19 km to the pass at 1240 metres above sea level. It was raining and snowing at the same time. The temperature was around zero degrees Celsius. The surrounding mountaintops were all covered in snow. Immediately after the crossroads, a police checkpoint and a barricade appeared. The road was closed! There was a lot of snow higher up which made the road slippery. Fearing that in such adverse weather conditions, lorries wouldn’t be able to make the ascent and end up blocking the road, or, worse still, drive off the cliff and into the abyss, the police decided to close the road in both directions. I didn’t ask when they were going to re-open. However, as a cyclist, I was allowed through. After all, if I was not able to make the climb, I wouldn’t block the entire road. The odds of me ending up in the abyss were also fairly slim.

As I was climbing higher, the rainy snow turned into proper snow. There was a strong side wind. At times, it pushed me forward with force that occasionally knocked me off my bike. Mounds of freshly shovelled snow rose a metre high on both sides of the road. At times, the falling snow turned into a blizzard. Visibility was only twenty to thirty metres. At one point, the road went downhill. I got off and walked, as it was slippery as hell and I was afraid to cycle. I was soaked through, not sure if it was from the snow or sweat. My poor quality gloves were completely soaked as well, and my hands stiff from the cold.

I started to feel hungry. I was glad that I had had a bit of glucose mixed with water plus the lifesaving sandwich at the start of the climb. Finally, the last 4 km downhill towards Berrouaghia. I was forced to stop twice as I couldn’t feel the brakes with my hands, which were stiff from the cold. Finally, I arrived at the town, shivering all over. Kids led me to “bain”, the local hammam, a bathhouse by day and a hostel by night (5 D per night). There was also a small restaurant nearby. The local people let me store my bike in a small stockroom. I had French fries and soup. Afterwards, I found out the meal was courtesy of the owner. Since leaving Algiers, I had cycled 120 km.

At the foot of the Tell Atlas mountain chain. First snow can be seen on the slope

16.01, Wednesday

I didn’t feel comfortable in the hammam. The Algerians roll out their mats and lie down for the night. I could hear conversations until midnight, perhaps later. The dim light shone all night. It may sound a bit silly, but I yearned for a wash and felt uneasy at leaving my passport and money unattended in this large, communal sleeping hall. Even though no one paid me any attention, I felt like an intruder. There were only men sleeping here, of course.

The bathhouse was open for women on different days, and on those days, men were banned from entering. Women seldom travel alone. If they travel with their husbands and family, they don’t stay in hammams. I have no idea where they stay if there are no hotels in town. The hammam is a feature of every Algerian town. Admittedly, hammams were not my first choice for spending the night, despite being quite safe and cheap.

Pitstop to stretch my frozen, rigid hands. I was not prepared for this kind of conditions. Snow! Wind! Cold!

The next morning, I woke up to a snow-slush-covered town: a dozen or so centimetres of snow, which was now melting rapidly. My clothes and shoes were still wet but there was nothing to be done about that, so I had to push on. The road was still under a lot of snow and very slippery. Cars were struggling even with the slightest incline. Lorries without snow-chains, and often completely threadbare tyres, are completely inadequate for such winter conditions in the mountains.

I witnessed a massive tanker slide onto the opposite carriageway in the melted snow and I briefly paused to take a photo. I then headed downhill and slowly left the snowy peaks of the Tell Atlas mountain chain behind. After a few hours of cycling, the snow was nothing more than a hazy memory of this morning and the previous day. I spent the night by the shore of the muddy lake (“szott”) in my tent. I much preferred this cold, orange home covered in ice, to the warmth and buzz of the hammam.

A street in Berrouaghia. Warm burnous, a long-hooded coat worn by the locals befits the weather conditions.

Huge tanker slides in the post-snow slurry

The further away from the mountains, the less snow…

17.01, Thursday

I reached Aïn Oussera in the morning. My breakfast was soup with a baguette followed by seconds, courtesy of the owner. I was gradually getting used to Algerian hospitality. In return, I left a pack of cigarettes. I carried a few of these with me as gifts; I got them from a duty-free shop. I don’t smoke myself. When asked if I used to smoke in the past, I replied: “Yes, almost two packs.” “A day?”, they’d ask in disbelief. “No, in my whole life.” I hadn’t smoked since I was sixteen years old, and this will certainly not change! What a waste of one’s health and money!

I had to cycle against the wind towards Hassi Bahbah. There were quite a few ascents on the way. I only managed 42 km in five hours. I had a soup in Hassi and carried on. Some dogs chased me. I tried to fend them off with a tyre pump, but I dropped it on the road (one of Victor’s tips: the pump should always be within easy reach, you never know when you might need it). By the time I managed to stop in a safe place, there was nothing but debris left, as the pump had been completely crushed by cars. I swore a bit too loudly. Oh well, what’s done is done. I had to get a brand-new pump in Djelfa (al-Ǧilfah). I found a cosy grove perfect for spending the night. I was 286 km from Algiers.

Snowy Tell Atlas mountain range

18.01, Friday

At eleven o’clock I arrive in Djelfa. So far, I had clocked 317 km on my bike, 295 km according to the map. I bought a new, Czechoslovakian tyre pump for 38 D. I now had a decent, metal pump. On the way to a hostel run by an Algerian guy, I met a priest from the White Brotherhood Order who spoke English and invited me over to his place. He had rooms for rent. There, I met a Polish guy who travelled by Landrover. Marcin from Krakow was travelling to Lagos on his own, as the rest of his crew had quit. He had $300 on him, a car full of grub and all sorts of goods for sale and exchange. At the time, he had taken a job as Professor Henri Lhote’s driver. Professor Lhote was well-known for cataloguing the Tassili n’Ajjer drawings and engravings. The Algerians didn’t care for him much. They said he had discovered something they had been well aware of for a long time.

Back in those days, Henri Lhote was coordinating research in the vicinity of Djelfa. There was a large number of engravings there, which were yet unknown to scientists. The Professor needed a 4WD with a driver and none of the locals offered reasonable hire rates. In this complicated situation, Marcin was a godsend. He was a bit apprehensive though, whether the Professor could actually afford his, fairly cheap, services. I have no idea if he managed to drive across the Sahara, I hope he did. I never met him again. During my brief conversation with the Professor, I found out that there was a large rock in the shape of a mushroom, about three metres high and five metres across. It was located not far from the main road, in the same direction I was heading in.

Underneath the “hat” of the mushroom-shaped rock, there were inscriptions dating back a few thousand years. I wrote down the directions carefully: 35 km past Djelfa, on the left-hand side, there is a road leading to Messad (Masad). 2 km down this road, there’s a right fork, which is just a dirt track with telephone cables on the left. If you take this track and follow it for 1,5 km, you’ll see the rock. It’s about 400 metres from the road. The inscriptions are not as spectacular as the ones in Tassili n’Ajjer, nonetheless worth the 2 km detour.

I was also given directions to another site: there’s a dirt track 2,5 km past Sidi-Makhlouf, 30 m away from the main road. There’s a path with a barbed wire alongside it, leading from the dirt road towards the main road. At this point, the barbed wire borders the main road as well. Follow the barbed wire from the dirt road towards the main road. After the ninth kilometre, there is a concrete barn without a roof. Follow the track for another 3 km and there, on the right-hand side, behind the dried-up stream (“wadi”), you’ll find four inscribed rocks.

A sheep wool dye-house in Djelfa (al-Ǧilfah)

19.01, Saturday

I was in Djelfa. It was bloody cold and windy. The frost was really getting to me. Djelfa is 1300 metres above sea level. It’s a small town with an old fort and a Christian cemetery next to it. Many graves date back to the nineteenth and twentieth century. Most graves are French, but I also found a Russian one. I don’t see any Polish names. I met a cyclist from Japan the previous day! He went on his way today, heading for Lagos.

The streets of Djelfa

The streets of Djelfa

Djelfa. Despite the frost, the men sit outside the coffee shop as it’s warmer out in the sun than inside the building

On a frosty day, even the men covered their faces

I would only photograph the women from a distance, when no one was looking

I was able to photograph the kids without any issues. The girls in colourful European outfits. The boys in traditional burnous coats, with denim jeans and trainers peaking from underneath.

I was able to photograph the kids without any issues. The girls in colourful European outfits. The boys in traditional burnous coats, with denim jeans and trainers peaking from underneath.

20.01, Sunday

I headed off to Laghouat. I couldn’t find anything else to eat, apart from French fries and a baguette for 1.5 D. The day was sunny, but there was a freezing tailwind. The cycling was going alright. I followed Professor Lhote’s directions and, after a couple of hours, I reached the mushroom rock. I found it without any problem. There were engravings on the rock depicting an antelope, an ostrich and other animals. Sadly, they were accompanied by contemporary Arab graffiti. I decided against going to the second site, where more engravings could be found. Next time, perhaps?

On the way back, I lost one of the rear spokes on a sandy track, which worried me. I had only cycled a few puny kilometres across rough terrain and had lost a spoke already. What would happen when I reached the end of the tarmac? I stopped for a quick soup in Sidi Machluf, for 3.5 D and found a decent place for the night. I pitched my tent in a post-groundworks trench. Hidden behind a heap of soil, I was completely invisible from the road. In addition, the wide trench provided me a wind shelter.

The rock with inscriptions in the desert by Djelfa: some date back thousands of years while others are quite contemporary…

When I mentioned my travel plans at the Polish People’s Republic Embassy in Algiers, the reaction wasn’t exactly encouraging. They warned me I might be robbed at night by drivers of passing cars. I didn’t let their stories get to me, but there was always a slight concern in the back of my mind. For this reason, at night-time I would always try to disappear out of sight and pitch the tent so it wouldn’t be visible from the road.

The rock with inscriptions in the desert by Djelfa: some date back thousands of years while others are quite contemporary…

At dusk, I was quite vigilant and looked around for anyone approaching, by car or on foot. Whenever the coast was clear, I would leave the main road and head away from it. The best shelter were the local bushes, but these were tricky to find at times. The next best option were rocks or large stones I’d be able to hide behind. If I were out of luck and couldn’t find either, I’d wait for nightfall. In the darkness, I’d walk 100–200 m away from the road. From such a distance, my tent wouldn’t be visible to passing cars. At that stage, I wasn’t using my “Juwel” petrol stove yet. Past Ghardaïa, when the distances between oases kept getting longer, finding a sheltered spot was easier. As a last resort, I would hide behind my tent when cooking.

Petroglyph on the mushroom-shaped rock

21.01, Monday

This morning, I got a flat when I was pushing the bike from last night’s campsite towards the road. What bad luck. A thorn puncture. I don’t have any particularly fond memories of Laghouat. A fairly big but anonymous city. Yesterday, I covered too many kilometres and spent the night too close to the city. As a result, I arrived in Laghouat too early and needed to wait for the restaurants to open. I had no choice, as at this stage opportunities to have a decent meal on the road were few and far between and it wouldn’t get better anytime soon. The instant soups I carried were far too precious to eat before reaching the most difficult stretch, after the tarmac ended in Tamanrasset (Tamanghasset). I had a soup and an orange dessert (6 D) and set off again. It was going well but, shortly after leaving the city, I got another flat. These thin, normal tyres are a curse. If I had had wider tyres, I would never have suffered from so many inner tube punctures.

The next place I reached after Laghouat was Tilrhemt. I could feel the day’s 90 km in my legs. It was five in the afternoon. I left behind the Saharan Atlas mountains before reaching Laghouat. The landscape was noticeably changing, becoming more monotonous: sparse hills, gravel, sand and clumps of grass. Some post-roadworks holes in the ground became my bed for the night yet again. I was not as comfortable as I was the previous night, but could not complain.

This isn’t a Palm Sunday procession. Date palm leaf is handy as a building material or firewood

This morning, I had to literally break my tent down again, as it was covered in ice. I wondered whether the English saying “to break up the tent” was inspired by such circumstances? It’s not a common thing in England to be folding a tent in freezing temperatures. After 20 km, I was forced to take a break. I caught a flat, again. That was two in one day again. The first one happened straight after I set off: after about 100 m, a stone pierced through the entire tyre. I still had the baguettes and jam from Djelfa. The Japanese cyclist caught up with me. He had left Djelfa a day earlier, but spent two nights in Tilrhemt. We travelled together for a few dozen kilometres and stopped for a rest in Berriane, where I took a few photos. We talked to local kids who were always the first ones to turn up whenever I stopped for a break. It was nice here. Berriane is popular with the Mozabites, although Ghardaïa, located some 40 km away, is considered their most important city. I set up camp 15 km from Ghardaïa. The Japanese guy carried on to a hotel in the city. His budget wasn’t as tight as mine.

A boy on a donkey near Berriane

PHOTOGRAPHY

I brought a Japanese Olympus OM-1 with two sets of lenses: a standard 50 mm and a 70–150 mm zoom. I also had a Soviet “Zenit”. I used the Olympus for colour and the Zenit for black-and-white photos. In East Berlin, I used East German Marks to buy twenty rolls of ORWO UT 18 film. I then topped this up with ten rolls of Agfa I got in the Netherlands. The Agfa film was better quality than the ORWO, but also much more expensive. I used ORWO NP 15, NP 20 (bought in the GDR) and Ilford PAN F (bought in the Netherlands) for black-and-white photography. Altogether, I took with me fifty rolls of black-and-white film. I would send my exposed rolls of film back home whenever an opportunity presented itself. The first chance I had to send my photographs back materialised in the form of a group tour from Krakow I met in Tamanghasset. Later, I met an English woman in a hostel in Kano. She was flying back home, so I asked her to post the box of my exposed film rolls to my friends in the Netherlands. The third parcel with film rolls reached home thanks to the help of Jolanta and Janusz Bukowski from Krakow, Polish doctors working in Bauchi, Nigeria. I also posted one parcel from Cameroon myself, as I preferred taking the risk of using their postal services than carry the rolls with me for months in the heat and humidity.

23.01, Wednesday