Uzyskaj dostęp do tej i ponad 250000 książek od 14,99 zł miesięcznie

- Wydawca: Wydawnictwo e-bookowo

- Kategoria: Literatura obyczajowa i piękna•Proza obyczajowa

- Język: angielski

- Rok wydania: 2018

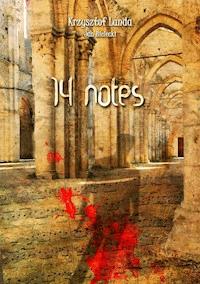

The Church has always been intrinsically linked to politics, although it would never admit that. Information is the most valuable commodity of the 21st century, a power which can be used to either create or destroy. It is behind the Vatican walls that strategies, and means that can change the world are being developed. One of them, stored on a memory stick, has exactly that power. Giuseppe, a long-serving employee of archbishop Luca receives a seemingly straightforward task of delivering the information to the Monastery. This information is more valuable than the life of one man and Guiseppe owes a debt of gratitude to the archbishop. A major threat to the Church turns out to be the Church itself. There is an enemy on the inside and hence special precautions are necessary.

Expect plot twists worthy of the best action films. Shootings, chases, murders ... A tense, deftly written thriller of goings-on in the highest ecclesiastical echelons. How much of it is fiction and how much a record of actual recent events? The authors depict the Vatican structures and customs with great fluency.

The Church is in dire need of reform but at what price?

Ebooka przeczytasz w aplikacjach Legimi na:

Liczba stron: 315

Odsłuch ebooka (TTS) dostepny w abonamencie „ebooki+audiobooki bez limitu” w aplikacjach Legimi na:

Podobne

Krzysztof ŁandaJan Bielecki

Fourteen notes

Authors:

Krzysztof Łanda

Jan Bielecki

Design and preparation of the cover:

TUV NORD Polska Sp. z o.o. (Maciej Kamiński)

Copyright © 2014 by Krzysztof Łanda; [email protected]

All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner.

All characters and events presented in the book are fictitious and the described events never took place. Any possible resemblance to natural persons is purely coincidental.

ISBN: 978-83-939273-6-4

Konwersja do epub i mobi A3M Agencja Internetowa

Part one

1.1

My name is Giuseppe and I am a humble man.

I wait patiently for the heavy door to open and archbishop Lucka to invite me to his office. Despite the time passing I don’t feel restless. The very thought of feeling impatient seems insignificant. Here, in the very heart of the Eternal City, whose stones witnessed the passing centuries, time seems to pass differently. Slower. Each time I pass the majestic walls of the Vatican I have the impression that the eyes of history follow me around.

This specific tingling in the nape of my neck continues. I feel it now, as I wait on the bench in the hallway, in the north wing of one of the administrative buildings of the Holy See, waiting for my audience.

I examine the office door. I let my eyes slide among the simple, hard door frame and solid door panel made of dark mahogany and imagine what it would feel like to slide my finger along it. I think of the slick surface and warmth of the precious wood, managing to resist the urge to come closer and stretch my arm out. I know that I am being discretely watched and such behaviour would come off as ridiculous.

I don’t have to imagine what is waiting behind the door. I remember every detail.

Someone once said that archbishop Lucka’s office has the same character as its owner and in a way expresses his personality. I couldn’t agree more. It is probable the dignitary’s every guest must have noticed this correlation.

I recall the sight of his office very clearly, as if I’ve been there yesterday. The spacious and elegant room has been decorated very tastefully; its host, despite his high position in the Vatican hierarchy, remained modest and resisted the temptation to surround himself with luxury and splendour. Nevertheless, the office made a great impression on me the first time I was there.

The central place of the room which I am about to enter is occupied by a large desk. It is always empty. Archbishop Lucka is known for his fondness for order; just as in his everyday work he does not need to surround himself with unnecessary, distracting scraps of paper, he does not allow himself to clutter his mind. Despite the many years that have passed, he is still considered to possess one of the sharpest minds in the Vatican. I can see him sitting at his desk, upright, with his eyes narrowed, carefully wording the reply to a difficult question with a serious, grave look on his face.

He is a man of shadow. Every time I was in his office, and there have already been dozens of such visits, it was always dim and heavy curtains covered the windows. That I also find quite significant.

Few people realise how important a figure archbishop Lucka is due to his function as Head of Division Two of the Vatican State Secretary. He is the de facto counterpart of the state’s Minister of the Interior. Not much happens behind the walls of the Vatican without him knowing; all strings come together in one place, behind that dark mahogany door. In the dimness of his office, archbishop Lucka takes decisions which are often of key importance to the functioning of the church-state. However, he never manifests what power he has and always keeps his distance. Just as he rarely lets sunshine lighten his office, he prefers to avoid being in the spotlight and, whenever possible, it is his personal secretary who handles all contact with media representatives. I can only guess whether it is caused by caution or just his reluctance towards public appearances.

The selection of paintings decorating the walls of his office is circumspect and symbolic. Along exquisite, in many instances centuries-old reproductions of works of masters of the Renaissance: Raphael Santi, Donato Bramante and Michelangelo, as well as Albrecht Dürer and Robert Campin (he would say that it did not seem proper to limit himself to Italian painters), archbishop Lucka would also include modern art.

I remember my first audience in his office. He noticed how surprised I was to see reproductions of Jackson Pollock’s art and he laughed out loud.

‘The fact that I wear a clerical collar does not mean that I am not interested in life outside the Church,’ he said. ‘And in art itself I see some sacredness, a divine element. The same one in all ages, just expressed by different means, a different artistic code…’

We chatted a bit about the history of painting, which helped us break the ice; we saw each other for the first time in a long while and I did not even attempt to conceal my intimidation, which was obvious particularly given the circumstances the previous time we met. The archbishop confessed that art history is one of his greatest passions, and contemplating exquisite paintings not only lets him relax and calms him down but is also a source of inspiration and energy that he needs for his work.

– Being around modern art is particularly valuable for a person in my position, dear Giuseppe – he said. – The Vatican cannot solely focus on celebrating the tradition, although, obviously, we must remember our origins. The Vatican must constantly face new challenges brought by the modern times, complicated as they may be. Hence the expressive abstractionist right next to the Renaissance masters. Art constantly reminds me of my tasks and responsibilities, Giuseppe. It forces me time and again to think outside the box.

I had to agree with that. As a person close to the Vatican I knew how wrong everyone was who thought that the church-state was a rigid creation which could not keep up with the pace of the modern world. Respect for tradition and ceremony, though important, does not preclude making use of the latest technological achievements. The Vatican never was against science and progress, contrary to many unfavourable opinions, which are usually expressed by those who don’t have the slightest idea about it.

From the room adjacent to archbishop Lucka’s office come the sounds of computer keyboards and telephone conversation chatter is audible time and again. That is the Vatican’s second face, usually unnoticed, and even if noticed, disdained.

It is the face of a methodical professional, radiant due to the glow of the computer screen rather than eternal light. Room Two, as it’s usually referred to, is filled with people. Many wear clerical collars, but not all of them; the archbishop also contracts many lay people. They live in various districts of Rome and when they enter the walls of the Vatican, they swipe their access magnetic cards. There are women among them. What is more, there are non-believers among them – when hiring employees to Section Two, the Vatican applies completely different criteria altogether. It is the elite, the best analysts, graduates of top schools, often with experience in international corporations. They perform their work diligently and professionally and for that they are handsomely rewarded. They collect and aggregate information crucial for the work of the head section of the Secretary of State. They sometimes joke among themselves at coffee breaks that they work in the most powerful enterprise of all: God’s Corporation.

I wandered what was occupying archbishop Lucka so much. Never before did I have to wait so long for an audience, usually I was ushered in at exactly the agreed hour. Meanwhile it was already a quarter past the appointment time.

The issues bothering the hierarch most certainly were not something mere mortals should be pondering about. On the other hand, in our curt conversation over the phone the archbishop insisted how important it was to meet today, so he must have been pressed for time.

I had never thought about it before. Was something extraordinary happening? Suddenly I have the impression that telephones in Room Two ring half a tone quieter than usually. The tapping sound of the keyboards strikes me as more nervous, arrhythmical, interrupted. Through the half-open door I can see people getting to their feet time and again. I can hear the thumping noise of chairs being moved.

But it’s probably just my imagination. A bit weary due to the waiting, although far from impatient. Who am I, anyway, to rush archbishop Lucka, be it even in my thoughts? Obviously, I simply started making up dramatic scenarios.

No need for that. I should, after all, remain calm and sharp.

And there I go: the dark door to the archbishop’s office opens. His personal secretary and assistant, Casemiro is at the door. The clerical collar almost glares against the backdrop of his elegant black shirt. With a polite gesture Casemiro invites me inside.

I enter the room, suddenly convinced that this meeting would be more important than all the previous ones.

1.2

All the details are there; the office looks exactly the way I remembered it. God blessed me with exceptional memory.

The archbishop is behind his desk. The drawn curtains bar the afternoon sunlight; only single light beams cut through the dusk. Strong, concentrated light from a lamp falls on the desk. Covering the windows despite the sunny weather is another sign of caution, is the archbishop afraid that spies with the right equipment could photograph the documents he is working on from afar? The curtains constitute a countermeasure against listening-in. Lasers reading the delicate vibrations of glass induced by sound of speech constitute regular working tools of secret services.

The hierarch rises from behind his desk and smiles mildly when he sees me. I move forward, accompanied by Casemiro’s watchful gaze and the inscrutable stares coming from the pictures on the walls. I still feel the tingling in the nape of my neck, which it is impossible to get rid off in the Vatican.

‘Giuseppe,’ says archbishop Lucka, reaching out his hand. We greet each other; he embraces me and gives me a pat on the back. I don’t reciprocate the gesture; I am far too humbled for that.

‘Your Excellency,’ I reply. My voice sounds stiff, far from natural; I’m surprised at myself.

The archbishop points me to the chair and I sit in front of him, with the smooth surface of the precious wood between us.

‘I am sorry to have kept you waiting. Certain…. events took place which somewhat disrupted my plans,’ the smile left his face. ‘That is why, yet again, I must ask for your assistance.’

‘Whatever you need, Excellency.’

The archbishop looked up, looks deeper into the room, towards the door. I don’t turn around and just hear fast footsteps and hasty words, someone came up to Casemiro and handed him something.

After a moment the assistant approaches the desk and stands next to me. He is holding a stack of print-outs.

‘Please forgive me, Your Excellency,’ Casemiro says. His smooth voice in unobtrusive and blends in well. This is the reviewed annex to the latest report prepared by group one.

The archbishop nods. He takes the pile of papers from the assistant and places it on the desk.

‘Forgive me, Giuseppe. I absolutely must read this document immediately.’

It seems to me that the hierarch is slightly nervous, maybe concerned.

‘But of course, Your Excellency,’ I say. ‘I understand perfectly. I will wait outside…’

I want to get up, but archbishop Lucka stops me with a gesture.

‘It will take just a moment, my friend. Casemiro, please serve some water, our friend must be thirsty.’

I am not thirsty at all but I don’t dare to refuse.

The archbishop starts reading. His focused gaze covers whole parts of the text like a scanner – quickly and methodically. For a moment the hierarch stops reading, looks me in the eye, sighs and goes on reading.

I realise that the situation must indeed be exceptional.

I don’t know any other person whose gaze would be that sharp and penetrating; a gaze there is no running away from.

I remember the first time I saw that gaze twenty years ago perfectly.

On that particular spring day I had tried to kill myself.

Being young, naïve and desperate, I was convinced that nothing could stop me from taking my life. I thought that the world had clearly showed me how unnecessary it finds me and continuing the farce that was my life was pointless.

The woman with whom I had wanted to grow old walked out on me. She left me. She made in clear that she was leaving for good. I realised that there was no point in fooling myself anymore and that there was no hope left. Paradoxically that brought me some relief by ending the emotional struggle I had been experiencing for weeks. I had nothing to fight for anymore. The realisation that it can’t get any worse can offer such strange, bitter comfort.

However, when I thought that all I had to do is endure the pain, waiting for time to heal the wounds, the Piccola Lirica theatre where I worked decided to let me go. Due to drastic budget cuts for the new season, the theatre’s profile was being changed. The classic repertoire was to be abandoned and my countertenor, although supposedly “quite possibly the most superb in the whole of Italy”, was no longer needed. I couldn’t possibly imagine myself doing anything else. Piccola Lirica was my second home. Naturally, finding employment in another theatre would just be a matter of time but that was not the point. I loved that stage, that backstage, the audience. I loved it all like you love a woman.

Today I obviously realise how limited I was at that time, but I felt unmistakably that I had just lost the two cores of my whole world and that I was falling into a dark, infinite abyss. Arduous rehearsals, voice tuning practice and endless repeating of the practiced songs and then looking forward to the première of a new show; the evening meetings with my beautiful Editt, her smile which made the cheap wine we drank taste like divine ambrosia – that was my whole life. Editt and Piccola Lirica defined me, made me who I was. By losing them I lost myself completely.

The sun was still low when I descended to the Termini subway station. The morning rush hour was over but it was still quite crowded, trains were arriving and departing, commuters were getting on and off. People preoccupied with their own affairs were headed towards the city; others were running towards the train station. Everything was happening somewhere beside me, as if behind thick glass and it didn’t concern me in any way. I was sitting on a bench, numb as a lizard after a cold, sleepless night.

At one point I felt an impulse; something told me I had nothing to wait for anymore. I got up from the bench. The loudspeakers had just announced the arrival of a train, the speaker asked the passengers to step away from the edge of the platform. A small crowd of luggage-bearing passengers had already gathered.

Moments later red headlights flickered and the subway train appeared.

How tempting it was, one jump and that’s it. The huge wheels would obliterate all my despair and all my pain. I wouldn’t even have time to scream.

I headed towards the edge like a sleepwalker. The train was approaching inevitably, the navy blue face of the train growing with every second. I had reached the very edge of the platform and was one step away from the tracks. I knew that if I chickened out, if I let the front of the train pass me, it would be too late and I would not gather up the courage to try again.

I closed my eyes for all my worth. I got a grip and flexed my muscles.

I jumped.

It’s not true what they say about your whole life passing through your eyes, about that movie made up of your memories. I didn’t feel anything.

At the last moment someone caught my arm and pulled me back onto the platform with a decisive move. I lost my balance and fell. At the same time the train, coming to a stop, slowly rolled passed me with a deep roar; it was slow by that time, hundreds of thousand kilograms were reluctantly losing momentum.

I realised what had just happened. I knew I wouldn’t have it in me to give it another try. I got up slowly.

The man who saved my life was standing next to me. He was looking at me with a focused gaze, slim-built, around forty. He was wearing a clerical collar.

I felt weak, as if I was about to faint. He approached me, firmly but politely and led me to a bench. I didn’t say a word.

He sat next to me. He was silent for a moment and then said:

‘The world is huge, son. Much greater than we usually realise. The fact that you can’t find a place for yourself just now does not necessarily mean that it is actually like that.’

He paused for a moment; the train departing from the neighbouring platform would have obscured the sound anyway.

‘My name is Lucka,’ he reached out his hand.

I shook it, although I could hardly do it. I was drenched in sweat.

‘Giuseppe.’

‘Are you all right?’

‘Yes,’ I lied.

‘I don’t believe in coincidence,’ he said. ‘God wanted us to meet today. My train from Milan was half an hour late. If it did come on time, I would have left the station over a quarter ago. In which case you wouldn’t have been around either, would you?’

I nodded.

‘And therefore,’ he continued. ‘God must have plans for you, son.’

‘I am not particularly religious...’

He smiled.

‘Do you think God ever minded that?’

We sat a few minutes more, talking. The priest was interested in me working for the theatre and performing in operettas; it turned out we appreciated the same outstanding vocalists.

Father Lucka gave me his business card. We said goodbye and I promised I would get in touch with him.

That is how our incredible acquaintance started; on that day I met archbishop Lucka and my life started anew.

I am still in his debt.

The archbishop puts down the documents he had just read. He observes me for a moment and nods thoughtfully. Then he speaks, in an unusually gentle voice. It creates a strange dissonance given how dark his words were:

‘Dear Giuseppe... It seems that we are in grave danger. We are staring to lose control over what is happening in the Vatican.’

1.3

There is silence for a while. It seems as if the archbishop’s words are echoing ominously within those elegant walls and yet I know that it must all be happening in my head.

I don’t say anything. Archbishop Lucka sees the expression on my face although I do my best to conceal my emotions. He smiles. Was it not for my theatrical experience, I probably wouldn’t be able to tell that it is an empty, forced smile. And yet it does do the trick: It nips my fear in the bud, before it really got to me.

‘So far the power remains in our hands,’ the hierarch speaks in a gentle, soothing voice. ‘If we act calmly and reasonably, there is no way we could lose it. The stakes are very high and in such situations the winner is the one who is guided by reason. We must react fast and reasonably at the same time. Any mistake will immediately be used against us.’

I can’t help but notice that when saying this, he is unknowingly drumming his fingers on the edge of the desk. After a moment he notices it and his hands freeze.

‘Obviously, I am getting anxious,’ he sees I’ve noticed; his smile gets wider. ‘However I can assure you that we’ve developed a plan for such circumstances a long time ago. We are very well prepared.’

I am tempted to have a look at the papers lying on the desk, which obviously were the reason of all that agitation. I resist that urge. They were not written for my eyes to see. I would have understood very little anyway and no good would have come out of that, excessive curiosity was always frowned upon in the Vatican.

And I know my place. I am a humble man.

The hierarch speaks on:

‘In a nutshell, your task, Giuseppe, will not be different from the previous ones. I am not asking you to do anything you haven’t done before.’

The archbishop reaches out to a desk drawer. He takes out a flash drive, a small, inconspicuous USB memory stick and weighs it in the palm of his hand.

‘Once again you are going to take data to the safe in the Monastery. Just like you’ve done dozens of times before.’

‘Certainly, Your Excellency.’

He hands me the flash drive. I fiddle with it.

‘In the beginning was the Word,’ the archbishop says. ‘And the Word was with God... The Word, that is information, is still the most potent power and is the basis of every act of creation... or destruction.’

I am holding what seems to be an ordinary flash drive which you can get for a few euro in every electronics store. Flash memory, a few gigabits, or maybe several terabits of virtual space are captured in that plastic cover.

The archbishop continues:

‘Today, in the third millennium, we sometimes forget how great that power is. We are flooded by words from every direction and the media feed us with more information than we can imagine. We are drowning in this noise, we are becoming indifferent. And despite that there still exist words which, if said out loud, would strike with greater power than an atomic bomb. There is more and more information that has the power to change the world...’

A thought goes through my mind – how much can such a small cube weigh? Ten, maybe fifteen grams? Certainly not more.

‘I am saying this so that you realise how important your task is, Giuseppe. The flash drive you received is sealed. Its content has to remain a secret, both for your safety and the best interests of our cause. What you need to know however is that never before has such important data reached the Monastery. There is no second integrated copy of this information. If it got into the wrong hands it would lead to a great misfortune. There is no one else I would entrust it with than you, Giuseppe.’

I am not asking any questions. It is obvious that the data in question must be of great importance. The less important data is transferred electronically; naturally after they have been encrypted multiple times; only the most important information is transported on actual data carriers. The threat must be significant if the archbishop decided to lock it in a safe in the Monastery. In a safe where it is bound to be secure. In a safe which can be opened with only one key.

And I am that key.

‘You know how much I trust you,’ he says. ‘This time, however, for the sake of your safety, you will go with two companions.’

‘Casemiro,’ he addressed his secretary standing further in the office, that silent ghost, whose presence I have almost forgotten. ‘Please fetch Davide and Klaus.’

Casemiro approaches the door without saying a word. He opens it and for a moment I can hear the muffled bustle in room two.

Soon after the door opens again. Archbishop Lucka rises from behind his desk; I get up as well and turn around.

Two tall, well-built men are standing next to Casemiro. Both are wearing cassocks, but their posture likens them more to sportsmen or soldiers than priests: broad-shouldered, with broad chests, they exude physical strength.

‘God bless, Your Excellency,’ they greet the host.

The archbishop introduces us.

‘This is Giuseppe, and these are fathers Davide and Klaus.’

We greet, discretely and respectfully. Both of them grip my hand strongly.

Father Davide seems a bit older. He has long hair tied back in a ponytail, although his forehead is high and his temples are grey. The wrinkles on his face are not deep but quite distinctive; my guess is he might be around fifty. His dark eyes are penetrating and mysterious; you can tell by those eyes that not only are his muscles are strong but his mind is sharp as well.

Klaus on the other hand cannot be older than thirty-five. He is a bit taller and even more athletic. He doesn’t look Italian. He has short, fawn-coloured hair and stubble. His grey eyes seem surprisingly cheerful, although his face is focused and serious.

Both of them look as if they weren’t priests at all and have just dressed up in cassocks.

The archbishop turns to them.

‘I would like you to accompany our friend on his way to the Monastery. The situation has become so serious that your knowledge and experience may prove necessary.’

‘Let us hope they won’t,’ Davide answers in a serious voice.

Until now, whenever there was a need to take documents or data carriers to the safe in the Monastery I was accompanied only by Casemiro. Never before has the archbishop granted me bodyguards.

‘It is my hope too that there will be no need for us to use your skills,’ the hierarch said. ‘However we cannot allow for even the slightest negligence.’

Invited by the archbishops’ gesture, Davide and Klaus sit on chairs prepared by Casemiro. They move quickly, precisely and resiliently; they look as if they sat around for just a second, watchful, ready to spring into action at any moment. The hierarch himself took his place behind the desk, scanning the documents with his eyes.

‘We adopted the shoaling strategy as you asked, Your Excellency. We are ready,’ Davide says.

I feel confused.

‘The shoaling strategy?’

‘Yes, Giuseppe, that is our best option,’ the archbishop sighed, as if he was still analysing his choice. ‘The shoaling strategy..., in other words the needle in the haystack strategy. We will distract our enemies, should they want to intercept the flash drive somewhere on the way.’

‘When do we start?’

‘Right away. Are you ready, Giuseppe?’ the archbishop asks me.

‘I am ready, Your Excellency.’

‘Splendid. You have to keep in mind at all times how important the task is,’ this time he addresses everyone. ‘We cannot make any mistakes. I am fully aware that you know your roles perfectly and that it would be inconsiderate of me to ask maximal concentration and involvement of you.’

For a moment he hesitates, considers his next words. He continues.

‘I am relying upon you completely, my friends. I trust you will return safe and sound.’

‘With God’s help, nothing can hurt us,’ Davide replies. The archbishop nods gravely.

He gets up first and we follow suit. I take out my mobile phone, turned off long ago, pursuant to the safety procedure, and put it on the desk. It cannot be tracked on the way.

Archbishop Lucka bids us farewell. Once again he puts on that theatrical, almost genuine smile.

‘Godspeed, my friends.’

We are headed towards the exit. I still feel that shiver-inducing stare and I don’t know anymore who is watching – the history trapped within these walls, God Almighty or archbishop Lucka’s enemies.

1.4

We are walking along the building’s corridors. Davide and Klaus’s heavy shoes strike an even, fast rhythm. I am one step behind them. Straight as an arrow, with heads up high and muscles flexed rhythmically under the cassocks, they really differ from the stereotypical Italian priest.

I am not convinced they have in fact been consecrated. Despite having served archbishop Lucka for a long time and therefore having seen a lot, it is easier to imagine them in the army rather than celebrating Mass.

We go a floor down. None of the priests and lay administrative workers we pass pay any attention to us. The building and its occupants are preoccupied with their own matters and nothing suggests that an ominous intrigue just began. We are passing rooms from which we can hear conversation chatter, tapping of computer keyboards, printers humming and coffee being brewed. An everyday office symphony.

I find it hard to keep up with Davide and Klaus. They rush straight ahead like pre-programmed robots; I have the feeling that quite soon I will be out of breath.

The next flight of stairs leads us to the basement. It is much cooler down here. We take the short corridor and come to a stop in front of the doors leading to the underground garage, protected by a combination lock. Davide enters the combination on the touchpad, there is a quiet electronic beep and the door opens.

In the garage there are ten black G-class Mercedes cars with privacy glass, parked at even intervals. The bodies glisten in the halogen lamp light. There is some movement, it turns out we are not alone in the garage. Some of the cars already hold a driver and two passengers, some others are being boarded. We greet each other with a nod; there is no time for pleasantries.

We also get into one of the cars. All of them are brand new; it’s the luxurious W463 version. I recognise the characteristic body line, although I never considered myself an automotive expert. All I know is that they are solid, durable and dependable off-road cars and have been manufactured for many years.

I don’t know why I think that, but this seems a choice archbishop Lucka would make.

Davide takes the driver’s seat, Klaus sits next to him. I take the seat at the back and automatically fasten my seatbelt.

Our car is parked in the second row, we cannot move before the car in front of us drives out. We do not have to wait long. The black cars, one by one, start their engines and enter the driveway.

I am impressed by how smoothly it is all happening. Obviously I had no doubts that the action would be carefully planned by archbishop Lucka, but only when seeing this precisely tuned mechanism in motion do I feel completely reassured. There is no room for coincidence here.

We set off. I notice that when the car moved, Klaus crossed himself and moved his lips to the words of a silent prayer.

We leave the garage and emerge into the warm afternoon. For a moment I squint my eyes before they get accustomed to the natural light.

I can see the cars in front of us take different directions. Davide makes a few seemingly random manoeuvres; he turns into narrower streets, until we reach Via Cola di Renzo. Ahead of us I can see one more of the archbishop Lucka’s cars, however it takes a turning soon after. We move toward the east, we are headed towards the river.

‘Where are we going?’ I ask.

Klaus looks at Davide, as if surprised by my not knowing.

‘To the Termini station,’ Davide answers. ‘We are going to take a train there.’

‘You probably usually went the whole way in the car,’ Klaus says. ‘I’m afraid that this time we can’t afford that. We will be covering our tracks as much as possible.’

‘So that’s the shoaling strategy, right?’ I ask. ‘Disperse as much as possible to fool the enemy?’

‘That’s right. – Each of the cars heads in a different direction. To the Ciamino and Fiumicino airports, to train stations and bus stations. One will go directly to the Monastery. Each car holds three people and a flash drive is carried in all of them. It’s just that nine of them are worthless and only yours is invaluable. That’s why we’ll disappear like a needle in a haystack. It would be difficult for the enemy to find us.’

Klaus adds:

‘It is the best strategy if you want to avoid confrontation and at the same time introduce some chaos and mislead the enemy. Otherwise we would have used the rhino strategy.’

‘The rhino strategy?’

‘You would have left for the Monastery in a heavily escorted armoured car. However today our enemies are conservatives within the Church hierarchy. So far they haven’t used force but we suspect that they are ready for that. Anyway, there are many groups unfavourable towards the Church. Not only the conservatives may try to intercept the flash drive. We want to avoid open combat. And even more so, a fire fight, God forbid. The risk is too great. Our intention is to get there unnoticed.’

‘But aren’t we risking much more that way? If it did come to the attack, we are far more exposed...’

‘The archbishop does not think that the enemies managed to set up an agent in his surroundings, he is absolutely sure of his people and furthermore he only shares his plans only with a very small group of people. And so the chances of the conservatives anticipating which car the flash drive is in are very slight. They would have to intercept all of them.’

Davide mumbles something to himself when a boy on a Vespa in front of us rapidly slows down. I can see Klaus getting tense, assessing the situation in a split second. The boy gets of the motorbike in front of a trattoria. Klaus, seeing that there was no threat, continues his speech.

‘We doubt that they have enough means to follow ten objects at one time, especially since there was no way they could expect such a swift move on our part. Had we set out in a convoy, it would have been a clear signal for them indicating where the target is. The journey to the Monastery only takes a quarter of an hour so they would have had a few hours to prepare an attack. The conservatives have a lot of power, Giuseppe. It would not be an exaggeration on my part if I said that they have quite an army at their disposal.’

‘Sometimes thicker armour does not increase the safety,’ I can see in the mirror that Davide is smiling. ‘A mountain eagle will catch a slow tortoise far easier than ten fast mice.’

I am quite convinced that the archbishop did indeed choose his best men. I do not know who Davide and Klaus are, but I am certain that they are every bit the professionals.

The Mercedes glides through sunlit Rome. The age-old tenement houses standing along the Via Cola di Renzo are basking in the warm beams of the sun. The roads aren’t particularly crowded and we don’t get stuck in any traffic jams. When we are waiting for the light to change, through the window of one of the countless restaurants I see young, careless people, laughing over wine. They weren’t rushing off anywhere. I think of myself like that from many years ago, about Editt and the many afternoons we spent, when I thought I knew perfectly well what course our life would take. I wonder when it was that I last saw her. I know for sure that she got married and has two children. God bless her, I hope she is happy.

We cross the Tiber via the Regina Margherita bridge. There are groups of tourists standing there, laughing, taking pictures. The river glistens with reflected sunlight.

We drive on. Soon after, Viale del Muro Corto surrounds us with lavish, dark greenery. We circumvent the Piazzale delle Canestre square and turn into Viale del Muro Torto. I know these streets like the back of my hand and yet I feel as if I am seeing them for the first time. We drive into a tunnel; after a moment in darkness we are covered by sunshine yet again. I wish I had my shades on me, they would certainly prove useful when we get out.

For a few more minutes I watch the Eternal City in silence through the window. I enjoy the sight of the building facades we are passing; I smile upon seeing bus number 310 with which I used to commute when visiting my late mother in her flat at Via Palestro. A thought comes through my mind – what if I never get the chance to see this most beautiful city again? I immediately try to forget about it.

Finally we reach our destination, at Piazza dei Cinquecento, the Termini train station. Davide parks the car and inserts a few euro in the parking meter. The car will be picked up in a few hours by the archbishop’s men.

‘We have seven minutes to the departure,’ Klaus says. ‘We already have the tickets. We could probably manage to buy some sandwiches’

Davide laughs. One would think we are going on a jolly trip rather than a mission on which the future of the Vatican depends.

1.5

I don’t know if everyone knows that feeling. Sometimes, just moments before something terrible happens, before danger strikes, comes a warning in the form of a sudden, alarming tingling. For a split second it takes your breath away, suddenly you are certain that it’s the moment. It might be a cue from God, maybe the touch of the Guardian Angel or some innate sense, unknown to humans. I myself experienced it twice, both times right before a car accident. I think that at least once it saved my life, when, probably only thanks to that tingling and the sudden focus it evoked, I managed to make a sudden turn and avoid a head-on collision with a truck, which suddenly drove into my lane.

I feel that tingling once more when we head towards the main entrance of the Termini station. “It” will happen in a second and I, in some supernatural way am aware of that and like a photo camera register every detail surrounding me, I suddenly see more and in a clearer way. I can see a thin, dark-skinned stranger with Arab-like features reach under his jacket and I know what will happen.

Shots will be fired.

Davide and Klaus react instantly. They shield me and swiftly reach for the guns they kept hidden under the cassocks. Sig-Sauer p226, a standard firearm of the Swiss Guard – I don’t know why that piece of information I heard sometime in the past now comes to mind.

Davide takes his aim and shoots. Klaus also took a shot and the stranger falls to the pavement. He is shaking his head, I think he’s alive; he might have had a bulletproof vest under his jacket. Everything is happening in a flash; there’s no time to think, I am completely confused.

Klaus takes a step back.

‘Run!’ he shouts.

He knows that there will be more attackers. And indeed, another dark-skinned stranger is aiming his gun towards us, this time from the direction of the station. He falls to the ground moments after, but before that he manages to pull the trigger; he must have a silencer because there was no bang.

Davide, who is pulling me to the side, at the very moment is flexed with a sudden jerk, we almost fall down.

‘It’s all right,’ he says to Klaus.

He drags me further, towards the entrance. The people around us are even more confused than I am, someone started screaming. Out of the corner of my eye I can see a dark pool of blood growing around the attacker on the ground.

Davide pulls me with more force. We run. Behind our back Klaus takes further shots and stops them. The fire fight continues, one shot just misses me; I feel a slight pull, it seems that the bullet went through my backpack.

After a few more steps Davide stops and turns around. He aims and shoots, one, twice, three times. I turn my head and see a person falling to the ground.

A moment later Klaus kneels, as if he was suddenly pressed towards the ground.

‘Run!’ he says again and then falls to the ground limply.

‘Klaus!’ I shout, but Davide decidedly tugs me by the arm. All I see is a red halo of thick blood bursting around Klaus’s fawn head.

There is no time for emotions.

Suddenly a figure in a grey jacket appears among the crowd of passengers whirling around the main entrance before us. A stone-like, Arab face. Davide pushes me to the side, at the same time the stranger takes a shot. The distance is just over a dozen steps; it seems there is no way he could miss.

Davide’s body twists unnaturally yet again, some force raises his left arm as if he was a ragged doll. It does not, however, put him of balance; I don’t even notice the slight move he makes with his right arm. Another shot is fired, unfortunately for the aggressor it was far more accurate this time; the stranger falls to the ground, dark blood gushing from his chest.

Even the fact of breathing his lasts breaths does not cause any emotions appear on his face.

At the same time, as if on command, panic breaks out. People scatter in all directions, shouting; children start crying.

Davide looks around.

‘Platform six, let’s go slowly,’ he says.

Pale, in a blood-stained cassock and a Sig-Sauer in his hand, he looks like the angel of death, the dark herald of the Apocalypse. There is chaos outside the Termini station; people are running in all directions. Someone falls, someone else cries hysterically.

Suddenly out of the passage runs a man – he has a dark-skinned face and grey jacket, just like the one shot in the station hallway a moment ago. He runs towards us and reaches to his waist. At the same time however, he wobbles and falls to the ground like felled timber; for a split second I saw a red dot moving along his clothes. Was it a sniper shooting?

Everything is happening incredibly fast.

It is real life, not a film set, after all. I wonder, frantically – where are the police, the Carabinieri?!

There’s another shot; someone is aiming at us. It is an Arab hidden behind an advertising column, a few dozen meters from us. Davide aims at him, he shoots twice but both shots miss. The man leans out, shoots and misses as well. Davide tries to shoot back and then we can hear the hollow click of the firing pin. He is out of bullets.

Davide freezes and the attacker can see it. He leans out from behind the column more boldly and takes an aim. This time he can’t miss, he knows all too well that we are defenceless. He hesitates as if he couldn’t decide which one of us he should shoot first.

He will never have the chance to make that call.

A red crest explodes around his head; his arms fly to the sides. The body falls to the ground.

Davide is taken by surprise but there’s no time to think.

‘To the train!’ he says.

No one stands in our way when we enter the hall and move from the passage to the platform. Davide looks around, watchfully.

The passengers are confused by the shots, the threat could be anywhere. It seems any one of them could be holding a hidden gun and waiting for us.

I have no idea why I am not terrified. My brain is flooded with adrenaline.

Our train is standing on the platform; the speaker has already announced its departure. Most of the passengers have already boarded and the platform isn’t crowded anymore.

Davide examines the surroundings, searching for any new threat.

He hides his gun under the cassock. We jump on the train; the automatic door closes behind us. The speaker announces the departure again and after a short while the train moves.

‘A sniper,’ Davide says. ‘We were saved by a sniper. He must have had his nest on one of the rooftops. But it can’t have been any of our men... The schooling strategy was a mistake. But we did not expect the Arabs to attack us. The conservatives yes, but the Arabs…?! The situation had gotten much more complicated. There are more enemies than we thought. The archbishop must learn about this…’

Only then do I feel how strong my heart is pounding. The backpack suddenly seems so heavy it could pull me to the ground. I lean on the door.

‘Are you all right?’ Davide asks.

‘Yes,’ I don’t even have a scratch on me.

He on the other hand is wounded in the shoulder, the blood soaking through the sleeve of his cassock.

‘Let’s go the bathroom.’ he says.

We get inside. I close the door behind us.

Davide takes off his cassock. Underneath it he is wearing a black, short-sleeved shirt. Blood is streaming down his muscular shoulder from two round holes, set close together, as if he was bitten by an enormous snake.

‘There is a first-aid kit in your backpack,’ he tells me. ‘Take it out, Giuseppe.’

There is not much space here. I take off the backpack which was hanging on one of my shoulders, unzip the pocket and take out the white box containing the fist-aid kit.

‘Now take out the gauze...’ Davide says. He looks at me and gives me crooked smile. ‘Better not. Just give me the whole thing.’

My hands tremble so badly that I can barely hold the kit. There is no way I would be able to dress his wounds. I hand him the kit without a word. Davide puts it on the closed toilet flap and opens it.

‘I was lucky, incredibly lucky’ – he says, moving his left arm. He clenches his fist, grimacing in pain. ‘No broken bones. God was watching over me.’

I see him dress his wounds quickly and professionally. He cleans the wound with an octenilin-soaked gauze, he grimaces because of the pain but there is not a word of complaint. Drops of sweat appear on his forehead and his breathing gets heavy. After that I help him put a bandage over a large stack of gauze which stops the bleeding. He gives himself a shot.

He sits down on the closed toilet flap.

‘Poor Klaus was not as lucky as we were,’ he says. ‘God forbid his sacrifice goes to waste.’

The train was gathering speed. We were leaving the station behind faster and faster.

‘Someone helped us,’ Davide says at last. ‘Someone I don’t know anything about. We must contact archbishop Lucka.’

1.6

Davide gets up, looks at his reflection in the mirror. He sighs and says:

‘I am afraid I will have to ask you to get us a phone, Giuseppe.’

At first I don’t understand what he means.

‘Get us a phone?’

‘Borrow it. Ask for a phone for just a second so that I could talk to the archbishop,’ he clarifies. Ask one of the passengers to lend you their mobile for a moment.’

He smoothes his hair out with his right, uninjured arm. A few grey strands of hair stick to his sweaty face. Davide is pale; I can only imagine how much the wounds hurt.

‘I would do it myself,’ he tries to smile. ‘But look at me... I don’t exactly look like someone particularly trustworthy, do I?’

I go to leave the bathroom immediately, but Davide stops me with a gesture.

‘Wait. You have a cassock ready in the backpack. Put it on.’

‘Me? In a cassock?’

‘Well, better that than a welder’s clothes, or something,’ Davide tries to joke. ‘We don’t have too many options here, so don’t be picky. There also is a black shirt for me, please take it out.’

He unbuttons his shirt with difficulty, grimacing every time he is forced to move his left arm. He opens the window wider. He folds the blood-stained clothes and throws them out of the window. He is standing there, wearing just his pants; broad, well-built, without an ounce of excessive fat on his flat abdomen. I look at the dressing on his shoulder. It clearly was put on very skilfully, as if by a doctor, as there are no signs of blood anymore.

I help him put on the fresh shirt without him asking me to. I can see he is grateful.

‘Thank you, Giuseppe.’

I also take of my shirt. Davide indicates that I should throw it out as well, and so I cast it through the window. Before I lose it out of sight, I can see it spread out in the wind like a huge butterfly.

I put on the cassock which was in the backpack. I struggle with the tiny buttons but finally make it. I look at my reflection in the mirror. I try to remember whether I had the chance to play a priest back in my time at Lirica Piccola; it’s quite probable but I can’t recall it right now.

‘Splendid,’ Davide says in a happy voice. ‘You look like a natural in this clerical collar. Go, I will be waiting here for you.’

I take the backpack with me and leave the bathroom. I am scared; I can’t hide this fact even from myself. I force myself to bring a friendly smile to my face. I want other passengers to see me as the kind-hearted, travelling priest I want to impersonate.

I walk along the carriage. I don’t think anyone recognised me as a participant of the shooting; no one pays any attention to it. I come to the conclusion that from inside the train many passengers could have completely missed the whole event.

I wonder who I should ask for help. The young girl with headphones on, looking out of the window and mouthing the words to a song? The boy sitting next to her, deep into his game on the portable console? I feel awkward at the thought of disturbing them. The middle-aged married couple in the opposite seats, both lost in their books? I look at the titles of the books and I can see that they are reading in English – so they are probably foreigners. I don’t know any foreign languages very well; I don’t want to embarrass myself. All the more as the husband is reading a popular science book by Hawking; I’m afraid he would try to draw me into a conversation. And so I walk on.

I can see a kind-faced woman in her forties, a little on the chubby side, sitting by herself. She is about to finish a conversation on the phone; thank God she speaks Italian. I wait a moment or two.

‘Excuse me,’ I start the conversation, smiling as warmly as I possibly can. ‘My name is Giuseppe, I am a priest... I have a big favour to ask of you.’

She looks at me and smiles.

‘Adrianna,’ she introduces herself. ‘How can I help you, father?’

‘I lost my mobile phone. I have no idea how it happened. I suppose it must have been at the Termini station, somewhere in the crowded underground passage... Someone must have taken it out of my backpack.’

The woman shakes her head in outrage.

‘There is nothing sacred anymore... To rob a priest, Mother of God, this world is crazy...’ suddenly she realises what she said and covers her mouth with her hand. ‘I am so sorry, Father. I somehow took the name of the Holly Mother in vain.’

‘That’s all right,’ I reassure her.

‘I understand that you would like to make a call, father?’

‘That’s just it,’ I nod and I come up with an excuse on the spot. ‘I have to call the curia. And my mobile phone...’ I throw up my hands helplessly. ‘You know how it is.’

‘Of course, I do. It’s just that... You know what? I think I would have a request of my own to ask of you.’

She looks as if she just had brilliant idea.

‘Oh, is that so?’

‘Could you...’ I can see her hesitate. She lowers her voice and looks around; she finished the sentence in a conspiratorial voice. ‘Could you hear my confession?’

‘I beg your pardon?’ I am completely dumbfounded.

‘Hear my confession. I would be very much obliged if you could administer the sacrament of Holy Confession.’

‘Here? On a train?’

‘Bishop Aldo, maybe you know him, once said in his sermon that the confessional is not a necessary element of confession. And you have such kind eyes... I have sinned, father Giuseppe, what can I say? I want to amend my sins, with all my might,’ she adds quickly. ‘It’s just that I am afraid that my regular confessor in Corchiano will not believe in my resolution, well, that’s not the first time I’ve sinned, and he would impose such penance that I would never manage to go through with it.’

I am impressed by Adrianna’s frankness. I just wonder how far I am allowed to go in this play. However, our mission is paramount to everything else; I feel a bit guilty but decide to play along.

‘All right’ I agree.

It turns out that Adrianna is a very resourceful woman.

‘Maybe you could hear my confession in the bathroom?’

‘Now wait a moment, lady... Child...’ I turn red. ‘Now how would that look?’

Adrianna blushes.

‘Of course, father... It’s me being stupid again. Gosh, that big mouth of mine has always caused me trouble...’

I sit next to her. Adrianna leans over and starts whispering to my ear. I can smell that she had finished eating a garlic-spread sandwich recently.

‘I am forty-six. My last Holy Confession was a month ago...’

She is worried. I can hear her hesitate, chose her words carefully.

‘I have offended God with numerous sins. I smoked cigarettes again,’ she confesses in such a voice as if she was confessing to murder. Her theatrical voice can be heard from the end of the carriage. ‘Father, I have smoked again!’

‘That is all right,’ I say, stupidly. ‘But, be quieter, my Child, quieter, by God...’ I bite my tongue.

‘I was unfair to my sons,’ she continues her confession. ‘When my younger one, Alessandro, preferred to go visit that French girl of his rather than his father’s grave during the anniversary...’

‘Details aren’t necessary, my Child,’ I protest faintly.

I can see people in the neighbouring seats look at us.

‘Are you sure?’ Adrianna looks doubtful. ‘Well, all right then... The worst thing though, Father, is that I had impure thoughts... And to make matters worse, it was in Church, during mass! My old school friend, Dario, was sitting in front of me...’

‘That’s enough,’ I interrupt her. She ceases talking.

‘Forgive me, father,’ her voice trembles. ‘I don’t know how I could have sinned so much.

‘Don’t worry about that, my Child,’ I speak in a reassuring voice. ‘Our Lord’s mercy knows no bounds. In his eyes these trespasses are nothing...’

‘How come?’

‘Just like that. Nothing happened, everything is all right. God loves you, Adrianna.’

She brightens up.

‘Well, that’s wonderful!’ she goes back to being serious immediately, though. Of course I want to mend my ways and ask that you assign my penance.

Nothing comes to mind and so all I say is:

‘It will be sufficient if you help a man in need, my child. I really have to make a phone call quickly... In private, it is a delicate matter.’

After less than half a minute I am back in the bathroom with Adrianna’s phone. Davide smiles when he sees me.

‘You took your time, Giuseppe!’ He takes the phone from me quickly.

I decide to spare him the details. Davide dials archbishop Lucka’s number, he knows it by heart. It seems like forever before the call goes through. I can see the tension on Davide’s face.

Finally the archbishop picks up.

Davide brings him up to speed on the events in the station and our current standing. He talks about the two groups pursuing us, about how the Muslims turned out to be an unexpected threat. For a moment there is silence, and then the archbishop talks for a long while. Davide nods in silence.

‘God bless, Your Excellency,’ he says, ending the conversation.

I wait for an update. Davide reports the hierarch’s words:

‘The archbishop has friends in the police. He will send officers to the Varese station, they will secure our safety. As the archbishop said, they will pay special attention to individuals of Arab decent, which is by no means surprising after the events at Termini, which are all over the news by now... We are safe at our destination station but the police won’t be escorting us to the Monastery, neither can anybody guarantee that enemies won’t try to attack the train station or the train itself...’ Davide looks at me closely. ‘And that means that from the city to the Monastery we will have to go on foot.’

‘That is quite the walk,’ I say.

‘I know, and to make matters worse, we are unprepared. Oh well. With God’s help, we’ll make it.’

I take the phone back to Adrianna. I find her glowing, as happy as if something wonderful had happened in her life.

1.7

The journey is a peaceful one. Nobody bothers us; it would seem that the tragic events at the Termini station never happened, that it was all just a bad dream. The shooting, the blood, the dead bodies – all that seems less and less real as time passes and we gradually distance ourselves from Rome. When finally, after almost five hours we approach the Varese train station, I feel as if we are going on a trip again. Maybe it’s a way for our minds to cope with the overwhelming stress?

Davide is in good shape, and given that he’s been shot today, great, actually. He is still a bit pale, otherwise he looks like any other traveller. Certainly nobody would believe that here stands a man who had just attended to his own gunshot wounds, without a medic’s help, in the train bathroom.

We don’t talk much along the way. Davide is deep in his thoughts, his face inscrutable. Every now and then he interrupts the contemplation to quietly say a decade of the rosary.

Adrianna passes by a few times when she heads to the bathroom at the end of the carriage. She always gives me a glowing smile. I feel that, although having acted in a good cause, I acted dishonestly towards her, I did something very wrong. My conscience is bothering me, which I find very surprising, given the fact that the things I saw today make misleading that kind-hearted woman a trifle. I think that when I get the chance to tell that story to archbishop Lucka, I will truly make him laugh.

Finally the train stops at Varese. It’s late in the evening, the sun has already set and it is getting dark. We get off; I can feel that it has gotten much cooler.